Throughout 2025, a global series of retrospectives, conferences, and screenings will celebrate the centennial of Paulin Soumanou Vieyra (1925–1987), a pioneering filmmaker, critic, and historian whose contributions remain essential to understanding what we call “African cinema” today.

Even with his foundational role, Vieyra’s legacy is often eclipsed by later generations of filmmakers. Subsequently, the centenary is an opportunity to reassess his impact—not only as a director but as an intellectual who shaped discourse around “African filmmaking” at a time when the very notion was still being defined.

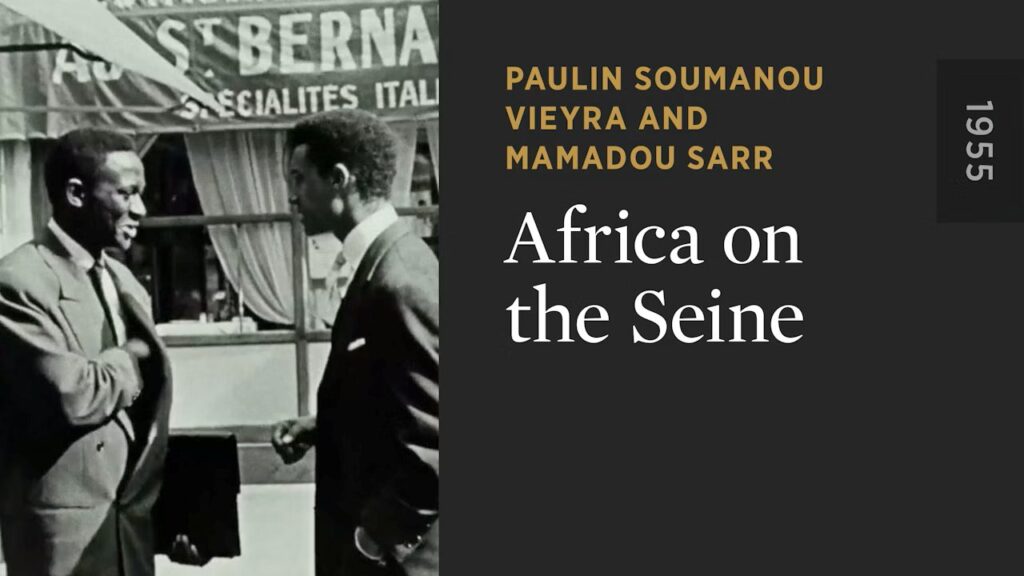

This year also celebrates the 70th anniversary of “Afrique sur Seine” (Africa on the Seine, 1955), the groundbreaking short film Vieyra co-directed in Paris with fellow Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC, La Fémis today) student Mamadou Sarr. Often considered one of the “first” African-directed films, it’s a work that challenges colonial restrictions, asserts storytelling agency, and serves as an artistic and ideological blueprint for later African filmmakers.

I admittedly had never really looked closely at “Afrique sur Seine’s” narration as a complete body of work—what is effectively a “mini-epic” poem—even though its verses are scattered throughout the film’s 22-minute runtime, rather than delivered all at once.

Earlier this week, I subscribed to Criterion Channel so I could access the film (as of now, the only place it’s streaming globally). Watching it again with fresh eyes, I realized how its words punctuate the film’s imagery, shaping its rhythm and meaning in ways I had not fully considered before. So, I wrote down the entire narration (French subtitled in English), and here we are!

Note: The original narration is fragmented across the film, but this version refines it for clarity and cohesion, while presenting it as a unified whole—a careful balance between faithfulness to the source and an interpretation that I believe brings out its deeper meaning.

It was a fun, instructive exercise!

Also note: I retained the term “Yellow” as it appears in the original transcript to reflect the historical and linguistic context in which the film was made, while certainly recognizing that the term is outdated.

The Words That Shape “Afrique sur Seine”

Facing the sun and the ancestors, we grew up sketching our independence.

The world around us remained unknown. We did not know the borders of our little corner of Africa.

We did not know there were other lands, where little Black children, little Yellow children, and little White children played together.

But we had our Niger River. Our sun. Our forests.

That was the time of innocence—the kingdom of children.

Children from all over the world.

How long ago was that? Does time even matter?

Here, the mist has replaced the sun.

Machines shape men more than nature does.

Paris is the center of dreams—of hope.

But Paris is also the city of broken promises.

For young people far from home, Paris holds an uncomfortable question:

Where are the golden roads from our childhood stories?

The roads we have found lead elsewhere—

To Rue de l’Odéon, to the House of Molière, to the Place de la Comédie,

Where, one morning, I encountered the civilization of outstretched hands.

But where do these roads truly lead?

To Paris of hungry days.

Paris of days without hope.

Paris of sidewalks filled with forgotten Black children’s fairy tales.

Paris of solitude.

And yet, Paris is incomparable in its diversity.

Paris, where fraternity is reborn.

A carousel of hope, spinning toward a bright future?

We come to discover Paris, to seek Afrique sur Seine,

With the hope of finding ourselves.

The hope of encountering one another.

The hope of civilization itself.

We salute the great minds, the men of liberty and equality.

The peaceful victories of peaceful men.

Paris, with all its monuments to humanity.

The world gathers in the Latin Quarter,

Trying to warm itself beneath the sun of love,

To tear down the ancient barriers of prejudice,

To dismantle the monuments of hatred.

To come closer, to understand one another,

Despite history’s falsehoods,

Despite a solidarity that is calculated,

A fraternity that is only principle, devoid of warmth.

Make way for the nourishment of the earth.

The fruits of the land. The fruits of culture. For all.

It is here, in this old quarter of letters and science,

That the wind of hope blows.

That happiness stirs.

And in the evenings, together at the banquet,

Friendship fills our plates.

Stomachs full. Faces bright. Hearts open. Hands outstretched.

Despite the world’s machinery, despite its traps.

Come, then!

Let us go forward, together—

Black, White, Yellow—

Dancing in circles of love,

Battling our way toward the light,

Before the face of God.

Reading the film’s narration in full—removed from its original context with dynamic imagery, sound, and cinematic rhythm—certainly alters how it lands; at least, I believe so, as a structured yet fluid, continuous reflection that invites interpretation on its own terms.

However, it’s also limiting, isn’t it?

Still, how does this shift change its impact for you?

The Film: An African Cinema Poetic Manifesto

“Afrique sur Seine” is something of a paradox within African cinema—one of the first African-directed films, despite not being made anywhere on the continent. It was made in Paris, France, as a result of colonial restrictions on African filmmakers. French colonial policies, particularly the Laval Decree of 1934, banned Africans from making films in their own countries—a policy designed to silence African voices.

The filmmakers responded cleverly: if they couldn’t film in Africa, they would turn Paris itself into a canvas for their storytelling. By placing Africans at the center of a film shot in Paris, they defied colonial restrictions on who could tell African stories.

More than just a creative workaround, the film arguably asserts itself as a manifesto—an intentional act of defiance as an African film made in exile, in a city that was a symbol of both colonial control and intellectual freedom.

“Afrique sur Seine” is not just about displacement but about the search for an evolving African identity that transcended borders—speaking to the authenticity, place, and authorship tensions that continue to shape African filmmaking today.

Though there is little documentation of Vieyra’s or Sarr’s intent to craft “Afrique sur Seine” as a visual poem, its structure, language, and rhythm align more with a lyrical meditation than with conventional documentary or narrative fiction.

The narration weaves together two contrasting emotional landscapes: the speaker’s idyllic past with their alienated present, and the struggle to maintain cultural connections while far from home. It speaks of childhood memories of Africa, captured in tender phrases like “Notre soleil. Notre forêt. C’était le bon temps. Le temps du royaume des enfants” (Our sun. Our forest. Those were the good times. The time of the kingdom of children), juxtaposed against the unpleasant realities of life as an exile in “Paris des jours sans pain. Paris des jours sans espoir. Paris de la solitude” (Paris of hungry days. Paris of days without hope. Paris of solitude).

The structure in “Afrique sur Seine” could then be appreciated as spoken-word poetry in cinema form. The moving images—Parisian streets, students, and random unnamed people—work like visual verses that complement the narration. This was groundbreaking for early African cinema, breaking away from colonial cinematic conventions, creating an experience that asks viewers to reflect and engage rather than simply watch passively.

As a poetic manifesto, whether intentional or not, the film declares African presence in a cinematic landscape that had rendered it invisible. It is not merely a nostalgic trip, but a direct claim to the right to tell one’s own stories.

Moreover, by portraying identity as fluid rather than static, “Afrique sur Seine” directly challenges Western cinema’s tendency to present Africa through an exotic, oversimplified lens. This reductive “single story” narrative about the continent is arguably still very much a concern even today, 70 years since the film.

In this way, the film anticipates themes that later African filmmakers like Med Hondo and Vieyra’s friend and professional colleague Ousmane Sembène would further develop—using cinema both as critique and as a way to rethink how Africa was depicted on screens.

Subsequently, this is more than just a celebration of a historical milestone. The film’s exploration of cultural alienation, yearning, and fragmented identities feels as urgent now as it did in 1955—maybe even more so in some ways: What does it mean to tell African stories, and where do these stories belong? What is an African film in 2025?

With a visual language characterized by fluidity, introspection, and resistance, “Afrique sur Seine” effectively sets up the question and offers its own answer: “African cinema” is defined by perspective and intent.

To be sure, the question remains open, but the film can serve as a reference point for filmmakers and scholars alike, urging an evolving reconsideration of how African cinema is observed and where its future lies.

Reflections and Unfinished Conversations

The words I’ve gathered and reshaped from the narration are just one possible reading. What emotions and insights does this poetic meditation stir in you? How might the film’s visual language speak differently today than it did in 1955?

As we mark Vieyra’s centennial, perhaps the most fitting tribute is to continue engaging with his work not as historical artifact but as a living text still asking essential questions about who creates cinema, where it belongs, and how it moves through the world.

An aside: A decade after Vieyra, another African cinema pioneer, Nigerian filmmaker Ola Balogun, would also turn his lens toward Paris. Like Vieyra, Balogun also studied at the IDHEC, although they were about ten years apart. His 1972 debut feature, “Alpha,” blends documentary and fiction to examine the lives of young Black intellectuals and artists in Paris during the post-independence era.

If “Afrique sur Seine” can be considered the first Francophone African film shot in France, “Alpha” just may be the first Anglophone African film to do the same—certainly feature film.

Both Vieyra’s and Balogun’s films subverted the ethnographic filmmaking conventions that had long shaped how “Africa” was represented on screen. Yet, while “Afrique sur Seine” is accessible, “Alpha” remains largely unseen. Last I checked a couple of years ago, the only known copy, a fading 16mm print, sat in the archives of the Cinémathèque Française, awaiting restoration.

If there’s documented evidence that Balogun and Vieyra ever met, I certainly can’t immediately find it.