It’s a question I hear often, at festivals, on panels, in interviews, in casual conversation, usually framed in different ways: What are your top African films? What have you been watching? What would you recommend? Give me your top 5 African films or filmmakers. The inquiry itself feels innocent enough. People are curious, and given my years of critical engagement with cinema of all stripes, not just African, it’s understandable why they’d ask.

But here’s the thing: I don’t really like answering this question. Or maybe I should say that I’ve become increasingly uncomfortable with it. It’s not that I don’t have films I admire or filmmakers whose work resonates with me. Of course, I do. The problem is that the question feels… incomplete. It’s a question that wants an easy answer—a list, a recommendation, a tidy summation of what “good” African cinema looks like. And I just don’t think it’s that simple.

To be honest, in some ways, I like to make it a challenge for the person asking. I don’t mean to be evasive or difficult for the sake of it, but I think there’s a lot of value in discovery—real, personal discovery. When someone gives you a list of films to watch, the process can feel transactional, almost passive. You tick off the titles, watch them, and maybe move on. But when you have to find your way, stumble upon works that resonate with you, follow the threads that intrigue you, the experience is different. You make it your own.

But maybe it’s the framing that bothers me. It feels reductive, as though films exist merely to be categorized as worthy of praise or unworthy of attention. But cinema—especially African cinema at this moment in our timeline—is so much more complicated and deserves something equally as complex instead of a binary response.

How do you compare a scrappy, low-budget Kenyan feature shot on borrowed equipment to a glossy $200-million Hollywood blockbuster? Should they even be compared? Are we judging both by the same standards? And if so, whose standards are those?

I’ll admit, part of my reluctance comes from a deeper, personal struggle. As an African living in the diaspora, someone who grew up in the U.S. but whose roots are firmly in the continent, I’m acutely aware of how my own tastes have been shaped by a mix of influences: American, European, Asian, and yes, African cinema. I grew up on the same Hollywood blockbusters as anyone else in the 1980s and 1990s, but I also have vivid memories of Nigerian TV series like “Village Headmaster” and “Cock Crow at Dawn.” My taste is a product of all those experiences, not some singular, fixed aesthetic rooted in one place.

And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that I’m still evolving. I’m not settled into a definitive idea of what makes a film “good” or “bad.” In fact, I’m less interested in those binaries than ever. I’ve started to think that as critics, as journalists, as cinephiles, our role shouldn’t be to judge films but to engage with them. To ask: What is this film trying to do? Who is it for? What does it reveal about its time, its place, its maker?

Take someone like African American filmmaker Tyler Perry. I’m not a fan of his films—at all. But I can’t ignore the fact that he’s tapped into something that deeply resonates with his audience. He’s built an empire around work that speaks to a specific community in ways I might never fully understand. My job, then, isn’t to dismiss his films outright but to try and understand why they matter to the people they’re made for.

This brings me back to African cinema. One thing I’ve noticed, particularly when this question comes from younger Africans, is how little awareness there is of the history of African filmmaking. Often, when people ask me what I recommend, they’re really asking for something contemporary—something that reflects their immediate experience. But African cinema didn’t start with Nollywood or even the wave of festival-friendly films from the last decade.

There’s a disconnect between the past and the present, and it’s worrisome. The pioneers who laid the foundations for African filmmaking, and those who came immediately after, are often unknown to the very people who might benefit most from their work. How can we fully appreciate where African cinema is today if we don’t understand where it came from?

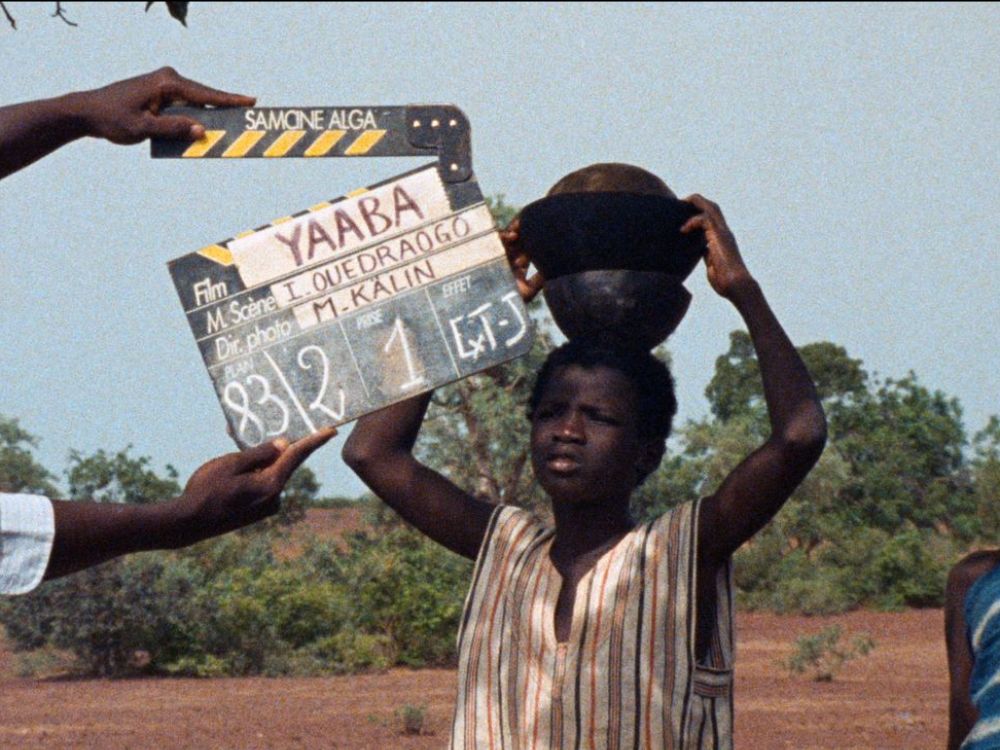

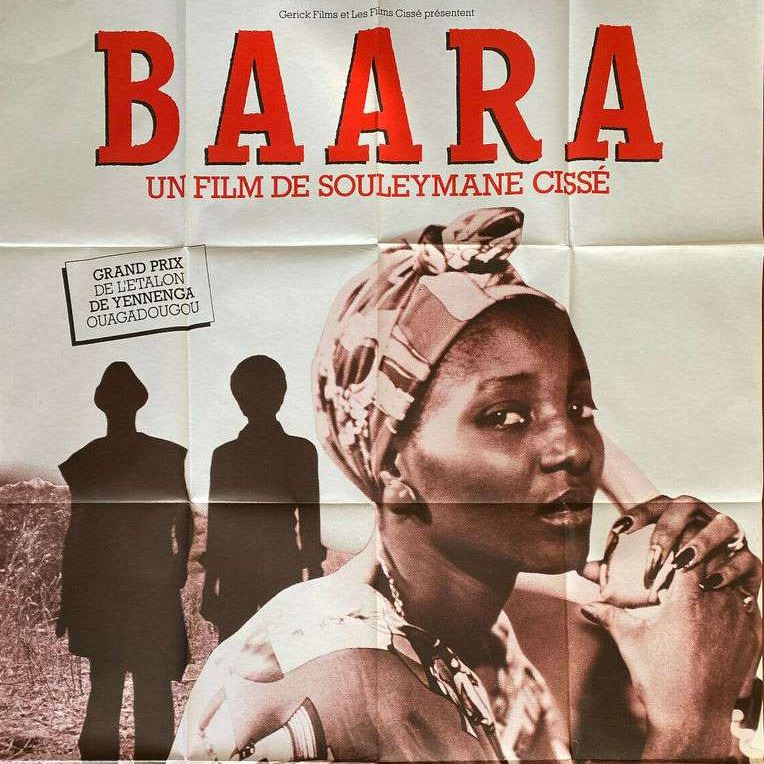

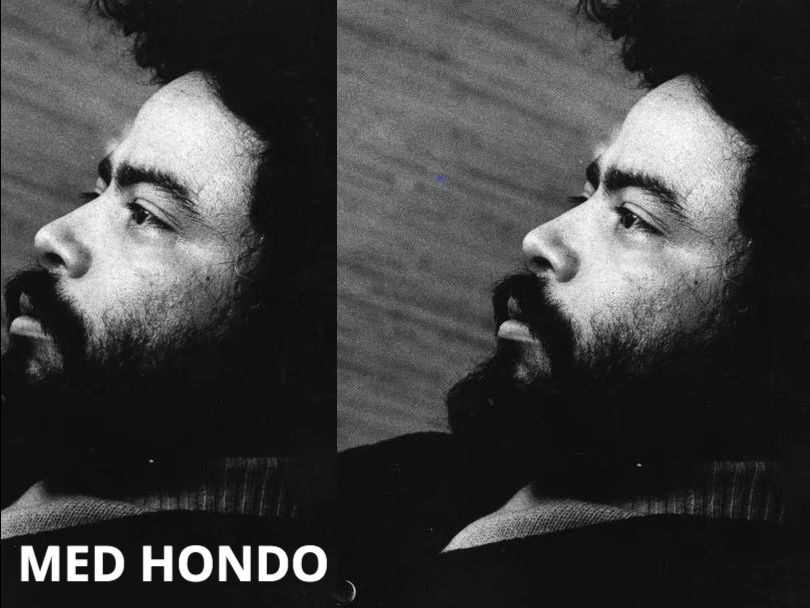

So, when I’m asked for recommendations, I often suggest starting there—with the pioneers. Go watch Sembène’s “Black Girl” or Mambéty’s “Touki Bouki.” Dive into Med Hondo’s fiercely political “Soleil Ô” or Safi Faye’s groundbreaking “Kaddu Beykat.” These films (and so many others), those that are accessible, aren’t just historical artifacts; they’re essential texts that still have something to say about the African experience today.

I don’t think the question I’m asked will ever have a definitive answer—and maybe that’s the point. But I do think we need to broaden the conversation. Instead of asking what I like, let’s talk about what a film is trying to say, how it’s saying it, and why. Let’s examine the layers—the budget, the audience, the filmmaker’s intent, the cultural and historical context. Let’s move away from the reductive good/bad binary and toward a more empathetic, curious, and nuanced way of looking at art.

Maybe that is the point of all this…

And for those who want to engage with African cinema meaningfully, my advice is simple: Start with the pioneers and work your way forward. Not because they were perfect, but because they dared to create something where nothing existed before. They wrestled with the challenges of their time, just as today’s filmmakers wrestle with theirs.

To understand African cinema, you need to understand that history—not as an academic exercise but as a way of connecting with the stories that brought us here.

So, what are my favorite African films? It’s complicated. Let’s talk about it.

Subscribe to Akoroko Premium for candid, contextualized, comprehensive African screen sector news, analysis, insights, criticism, and conversation: https://akoroko.com/subscribe/