“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” ~ Audre Lorde

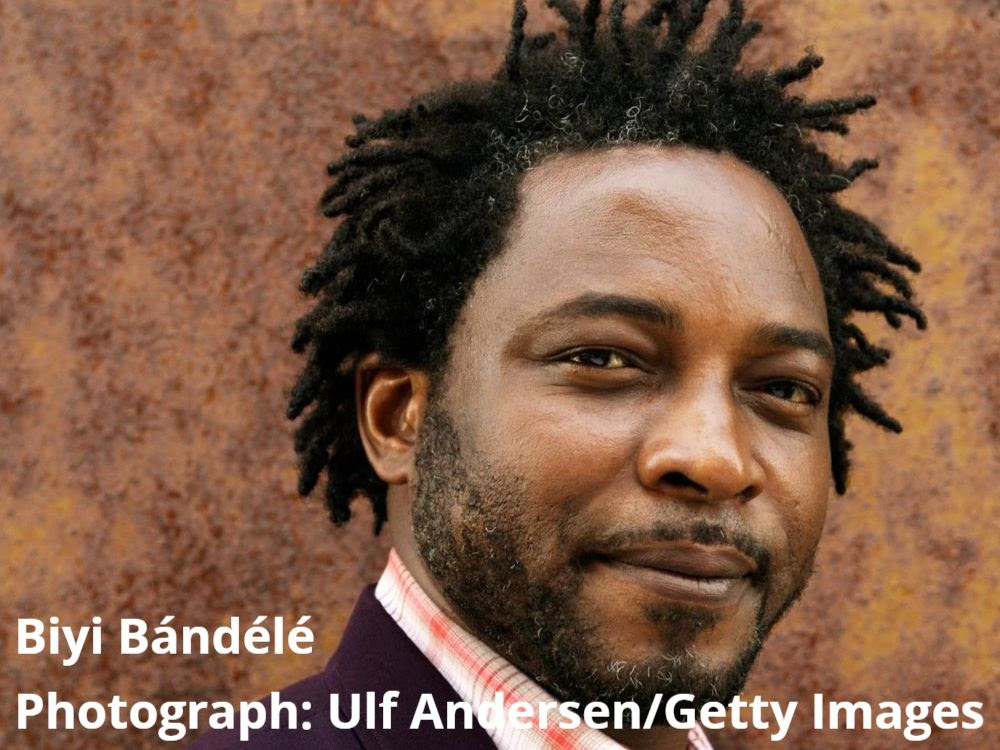

The term “creative restlessness,” as I use it, encapsulates what I see as the defining trait of Nigerian filmmaker, playwright, and novelist Biyi Bándélé’s artistic journey. His death by suicide, recently revealed in The Guardian (UK) article published on October 13, 2024—two years after widespread speculation—has both shocked and provoked a broader conversation about the pressures faced by artists like him.

The piece, featuring interviews with his daughter Temi and his friend Kwame Kwei-Armah, portrays Bándélé as someone driven by an insatiable need to explore new forms and narratives. This “restlessness” allowed him to create works that spanned novels like “Burma Boy,” film adaptations of “Half of a Yellow Sun,” and plays such as his adaptation of Wole Soyinka’s “Death and the King’s Horseman.”

Though I never met Bándélé, never interviewed him, and certainly didn’t know him personally, I found myself wrestling with how to write about this week’s revelations and the conversations around it. As someone who also experiences a similar kind of “creative restlessness”—my way of summarizing the driving force behind his artistic life—as seen in his fluid transitions between novels, plays, and films, it feels especially poignant.

This trait can be read as both a powerful force that drove his expansive body of work and a burden that perhaps became too much to bear.

His story is emblematic of the pressures many African artists face: navigating between personal expression, dual identities, the weight of representing their cultures, and the often conflicting demands of the global creative landscape, in a world that often insists on reductive categorizations.

Therefore, Bándélé’s “creative restlessness” is a fascinating concept when examined within the broader framework of African artistic expression. The term is inspired in part by The Guardian article and the words used to describe the artist by those who knew him, particularly in the Brittle Paper tributes that poured in soon after his passing in 2022, titled “100 African Writers Celebrate Biyi Bandele’s Life and Work.”

Soyinka’s reflection on Bándélé captures the very essence of this restlessness. Soyinka—who was a close colleague of Bándélé—described him as someone who “drove himself—hard! Too hard.” He believed that Bándélé’s constant ambition to push boundaries in different creative forms, whether through novels, filmmaking, or photography, was central to his identity, though perhaps it came at a personal cost.

Soyinka added that the stress Bándélé endured was palpable, and perhaps contributed to his untimely passing.

Similarly, Okey Ndibe’s reflection speaks to Bándélé’s ability to “bridge boundaries with ease,” referring to his capacity to work across genres and categories, and to move between cultures with his work. Ndibe referred to Bándélé’s creative energy as something that “seemed boundless,” describing him as someone driven by the conviction that he could extract something valuable from his crumbling society.

Moreover, Ben Okri’s tribute foregrounds the “generosity” of Bándélé’s artistic gifts, but also subtly touches on the burden of being a prolific and admired artist in multiple mediums. Yet, Okri also acknowledged that Bándélé’s “restlessness” was what set him apart, as he never stopped seeking new ways to express himself through his work.

This particularly resonates with those of us who allow our creative endeavors to consume us, no matter the cost. It speaks to an uncompromising vision, which in the African context often means navigating a much more challenging path; to the adaptability required of African artists navigating personal, social, economic, and political landscapes.

The balance between creativity as an essential form of survival and expression, and the potential burdens it places on the artist, becomes even more apparent when contextualized against the backdrop of colonial legacies, the fight for cultural identity, and modern-day market expectations.

Historical Context: Creativity as Survival

African artists, especially those working within colonized or post-colonial contexts, have historically used creativity as a means of survival—both literally and metaphorically. During colonization, they were marginalized, their work reduced or dismissed by colonial powers as inferior.

Creativity thus became a form of resistance, an assertion of identity in the face of erasure. Fellow popular Nigerian artists like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, as well as Kenyan Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, used literature, theater, and other artistic forms to counter the colonial narrative and assert the vibrancy of African cultures and histories with unwavering authenticity.

Bándélé’s work arguably fits squarely within this tradition of resistance. His stage adaptation of Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” and his exploration of Samuel Àjàyí Crowther’s life in “Yorùbá Boy Running” both suggest a desire to reclaim African stories from the margins of history, re-centering them within the global narrative.

But unlike earlier African artists who worked almost primarily to challenge colonial narratives, Bándélé’s creative restlessness appears to stem from a broader need to explore the multiple identities he carried—Nigerian, British, and globally African.

Present Day Pressures: The Burden of Expectation

Today, African artists like Bándélé face a different kind of pressure. While colonialism has formally ended, many African nations still struggle with the legacies of economic exploitation, cultural suppression, and political instability. African artists (particularly filmmakers) often find themselves caught between the desire to remain authentic to their cultural heritage and the need to appeal to global audiences, notably Western gatekeepers.

Bándélé’s adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun” speaks directly to this tension. The film, which took years to produce, was an effort to bring an authentically Nigerian story to a global audience, but it faced mixed reactions from Western critics and struggled with distribution.

The risk in navigating this balance is that African artists may feel compelled to conform to Western ideas of what African stories should look like or which African stories are worth telling, in the interest of survival, thus losing some of the authenticity that makes their work powerful in the first place.

Bándélé’s “creative restlessness” could be seen as a response to these pressures. His insistence on constantly evolving his craft may have been a way of resisting the very categorization that many African artists feel.

His adaptations of both Western and African literary classics (Lorca’s “Yerma,” Behn’s “Oroonoko”) demonstrate his refusal to be boxed into a single identity or narrative. He was a storyteller at heart, driven by a seemingly insatiable curiosity and the need to explore.

But with this creative freedom comes a kind of anticipation to be all things at once: representative of Africa, yet appealing to the global market; traditional, yet modern; political, yet entertaining; and still somehow considerate of one’s motivations which manifests in an artist like Bándélé as an intense pressure placed on oneself to explore new forms and challenge conventions.

Future Reflections: The Way Forward for African Artists

Looking to the future, the concept of “creative restlessness” as a survival mechanism for African artists raises questions about how we will continue to contend with the global cultural landscape and the economic needs of the marketplace.

Bándélé’s death by suicide, just one day after completing “Yorùbá Boy Running,” might offer a sobering reminder of the toll that such “restlessness” can take on an artist’s mental health and personal well-being. The pressure to produce, to constantly go beyond expectations, blaze new trails, and to balance multiple identities can be exhausting, especially in a world that still struggles to understand the complexities and varieties of African creativity broadly.

African artists will need to continue to embrace the fluidity that Bándélé embodied, using their work as both a reflection of their heritage and a means of engaging with worldwide narratives. However, it will also be important for the African artistic community to push back against the perceived need to conform to Western standards or deliver neatly packaged “African stories.”

The growing number of African contributions to global cinema, the art, and literary worlds provide a space for this kind of self-determination, where African artists can speak directly to African and diaspora audiences, but also engage with non-African and global communities, without the mediation of Western institutions.

A Lasting Legacy

This year, on June 30th, 2024, friends, family, collaborators, and admirers of Bándélé gathered to celebrate the launch of “Yorùbá Boy Running,” his final novel, posthumously published nearly two years after his passing. The well-attended and covered event, held at Brixton House in London, spoke to Bándélé’s impact.

“Yorùbá Boy Running,” a vivid reimagining of the life of Samuel Àjàyí Crowther—the Yoruba linguist and the first African Anglican bishop, known for his work in translating the Bible into Yoruba and his efforts in spreading Christianity and education across West Africa—reflects Bándélé’s own creative ethos, summarized as layered, boundary-breaking, and much engaged with African history.

The release of “Yorùbá Boy Running” can be observed as a sobering closing chapter in Bándélé’s career, yet the conversation surrounding his work and impact is far from over. In many ways, this novel is a final invitation to engage in the kind of multi-dimensional discourse that defined his life’s work.

Bándélé’s life seemed to be marked by a constant search for new forms of artistic expression, the “creative restlessness” I refer to, that will continue to inspire generations of African artists—both the incredible possibilities and the immense pressures amid an ongoing redefinition of what it means to create from an African perspective.

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” ~ Audre Lorde

I feel that many of us need to have these conversations around mental health, and not to mention the actual danger that artists on the continent often face from government regimes who may not like our depictions or what we are saying. “Check on your strong friends” has a whole new meaning…may Biyi rest in Peace.