Prefer to listen? This newsletter is now available in an AI-generated audio format. (11 minutes)

Akinola Davies Jnr’s “My Father’s Shadow” is less a narrative in the traditional sense and more an atmospheric record of a particular place, time, and mood: Lagos, June 1993, when Nigeria thought it would elect a new democratic president. The film is set against a volatile historical backdrop, but what Davies captures isn’t the politics as much as the emotional, intimate texture of family, distance, and longing.

But it doesn’t begin gently. The film opens in the register of a thriller: jagged archival footage, blackout cuts, military visuals, and dissonant audio that suggest instability rather than nostalgia. The grain of the 16mm film stock intensifies the atmosphere. Davies repeats the motif throughout—sudden silences, an at-times unsettling score, and moments that feel slightly out of phase with realism.

The film drops surreal markers as it moves: fighting crabs on a beach, a rusted ship half-submerged off the coast, people bathed in all-white garments kneeling and praying on windy sands, a dead whale on the shore. These aren’t explained. They aren’t metaphor in the traditional sense either. They feel like memory fragments, not “there to mean something.” Instead, they feel remembered—the kind of inexplicable, sensory-heavy moments from childhood or trauma that imprint on someone not because they’re important to the plot, but because they were vivid, strange, or emotionally charged. The film’s structure itself reflects this: not linear, not dreamlike, but suspended between both. This much may take its time to become clear.

The story follows Folarin, a father reentering the lives of his two pre-adolescent sons—Remi and Akin—after a seemingly long enough absence. He appears without warning. (Remi later repeats something their mother told them: that even people who love you, like God, can be hard to see.) When Folarin asks where their mother is, the boys tell him she’s gone to the village. There’s a brief exchange about whether he should wait for her, but he doesn’t. Instead, he tells the boys to come with him—he doesn’t want to leave them alone. That decision frames the rest of the film: a father suddenly present, a mother temporarily out of reach, and two boys pulled into an adult world they barely understand.

What begins as a seemingly simple trip to Lagos for Folarin to collect six months of unpaid wages becomes a full-day odyssey across the city with his children. They move by danfo (buses), by ferry, on foot, on okada. The dialogue is restrained. Exposition is minimal. The weight of the story is carried visually—the kinetic motion of the city and the pauses between words, inside public spaces, long silences while characters wait, listen, or observe. Davies builds the narrative like a procession, not a plot, but one that quietly gathers urgency as the day unfolds, moving toward something that feels inevitable.

Folarin, played by Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù, is presented without fanfare. He’s not framed as a hero or a villain. He has little time, few words, and possibly too many regrets. His sons—played by real-life siblings Chibuike and Godwin Egbo—respond with a mix of curiosity and guardedness. Their acting is unpolished but credible, which works. They’re not delivering dramatic turns. They’re observing, absorbing, trying to decode what kind of man their father is. The language shifts fluidly between English, Yoruba, and pidgin. Davies keeps the dialogue spare, letting silence and sound design communicate the emotional gaps. Their connection to the father is not immediate; it flickers, then retracts, then flickers again.

Shot on 16mm, the film captures Lagos with density and physicality—grain, contrast, heat, and movement. The production design locks the viewer into the early ’90s, not just with military checkpoints and radio clips, but with period-correct clothing, signage, and posters of football legends like Rashidi Yekini. For a two-minute stretch early on, Davies leans entirely into atmosphere: a long bus ride, movement through streets, markets, activity, music, horns, and clamor bleeding into open air. The sound mix is confident. The city is a character. Lagos feels vast and alive, chaotic but beautiful, worn down but vibrant. It demands negotiation. The people adapt. Folarin is still trying.

One recurring element is a nosebleed. The father’s. It first appears without comment. Later, at a military checkpoint, it becomes a trigger. A soldier stops them, convinced he knows Folarin. Folarin insists he’s mistaken. But when the bleeding returns, the soldier recalls Bonny Camp. For viewers unfamiliar: Bonny Camp is a real military cantonment in Lagos. In 1993, it was associated with repression and rumored mass killings following the annulled election. A radio segment in the film references a massacre there. The soldier says no one escaped. Whether Folarin did, or whether he was involved in something darker, is never clarified. Davies doesn’t fill in the blanks. But the moment sharpens Folarin’s character: he’s not just emotionally distant, he may be historically implicated—and he may be running.

The rest of the film is about avoidance. Folarin’s past. His infidelity (implied during an encounter with a waitress who seems to know him too well). His failings as a father. The older son picks up on it. Later, he confronts Folarin—“You always make her sad… you always leave her”—referencing their mother, who only appears in brief flashes throughout the film and then fully at the end. Her absence, both literal and symbolic, not as a character in action but as a visual interruption—possibly imagined—frames the day. By the end, it isn’t clear whether it’s a flashback, a vision, or simply the end of the memory.

The film unfolds almost like a road movie, but that framework is slippery. If the story is remembered, or imagined, the fragments make more sense. The surreal insertions, tonal shifts, and occasional timeline disruptions can be read as emotional logic. Davies is not recounting what happened. He’s replaying a last day, trying to make it last, trying to make it mean something, reconstructing memories. That reading aligns with the film’s origin. The script began years earlier as a private letter Wale Davies—Akinola’s brother and co-writer of “My Father’s Shadow”— wrote to their father after his death, in an attempt to process grief and preserve memory. Akinola later helped shape it into a screenplay, and eventually into a narrative structure: something remembered, reimagined, reassembled.

The specificity of location—the National Theatre, the Third Mainland Bridge, a beach amusement park—anchors the story in Lagos, but its emotional movement is inward and unresolved. Lines like Folarin saying to his sons, “Everything is sacrifice. You just have to pray you don’t sacrifice the wrong thing,” land more as exhaustion than wisdom. One monologue—Folarin’s memory of his brother, who drowned in the ocean, functions as a quiet eulogy for lost time. A stranger once told him that his brother’s spirit was sad, because no one remembered him. So he named his son Remi after him. It’s a story about grief, but also about unfinished obligation. The logic of spirits, dreams, and signs exists alongside traffic jams, wage disputes, and broken families. It all makes sense within the cultural logic the film occupies.

That also includes religion, present throughout, but never foregrounded. Background prayers, references to God’s will, prophetic declarations from strangers, and the boys’ own questions about life and death all run quietly through the film, treated as part of how people live and speak. Essentially, the spiritual, the superstitious, and the sacred sit alongside the political and the personal, with no distinction made between them.

What the film doesn’t do is offer tidy catharsis. The final act is abrupt. The father doesn’t come through in the way we might expect, and there’s no grand climax. Viewers who expect narrative closure may find the ending unsatisfying. But that abruptness seems deliberate, likely meant to mirror real life: unfinished, unresolved, often confusing. It might also reflect a gap—something the sons don’t remember, or weren’t present for. Given the film’s origins in a letter written by one brother to memorialize their father, the missing scene may not be an omission, but a limit of memory. It lingers as a recollection of a day that didn’t go as planned, but that didn’t quite burn itself into memory.

Technically, the film is sharp. Editing is patient. Sound design is minimalist but tense. Music is used sparingly, sometimes resembling ambient post-rock, sometimes just silence and room tone. Scenes stretch. Time wavers. Davies avoids sentimentality even in the most emotionally exposed moments. Ultimately, he’s remembering a father. Or what it felt like to lose one. Or to not really know him at all. The father is gone before he’s understood. But the boys remember enough to imagine him. That may be the whole point.

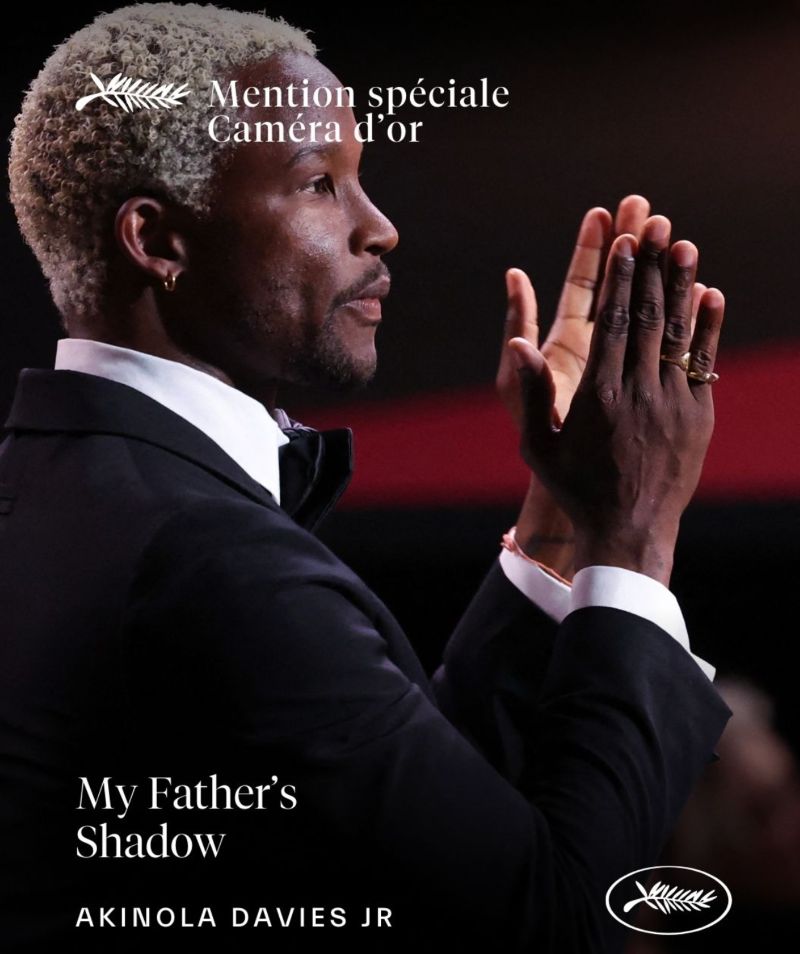

From a production standpoint, “My Father’s Shadow” is built on international alignment: UK backing, a Nigerian setting, and festival strategy geared toward global arthouse. The script was developed over years. Funding came from BBC Film and the BFI. The production was led by Element Pictures (Ireland) with local support from Fatherland Productions (Nigeria). It’s the first Nigerian film ever selected for Cannes’ Official Selection. Distribution rights were secured by MUBI and Le Pacte before the premiere, positioning the film for theatrical release in Europe and likely the US, and streaming in global markets. I expect a Nigerian premiere eventually—possibly sooner than expected, considering Mati Diop’s push for “Dahomey” to be seen in Benin and Senegal before any American or European release, and the fact that MUBI also distributed that film.

My Father’s Shadow had its world premiere in the Un Certain Regard section of the 78th Cannes Film Festival and will be theatrically released in France by Le Pacte, with global rights (including the UK, U.S., and other territories) acquired by MUBI.

For more exclusive Akoroko Premium coverage and intelligence on African screen industries, subscribe at the link. 7-day free trial and localized pricing now available: https://akoroko.com/localpricing/