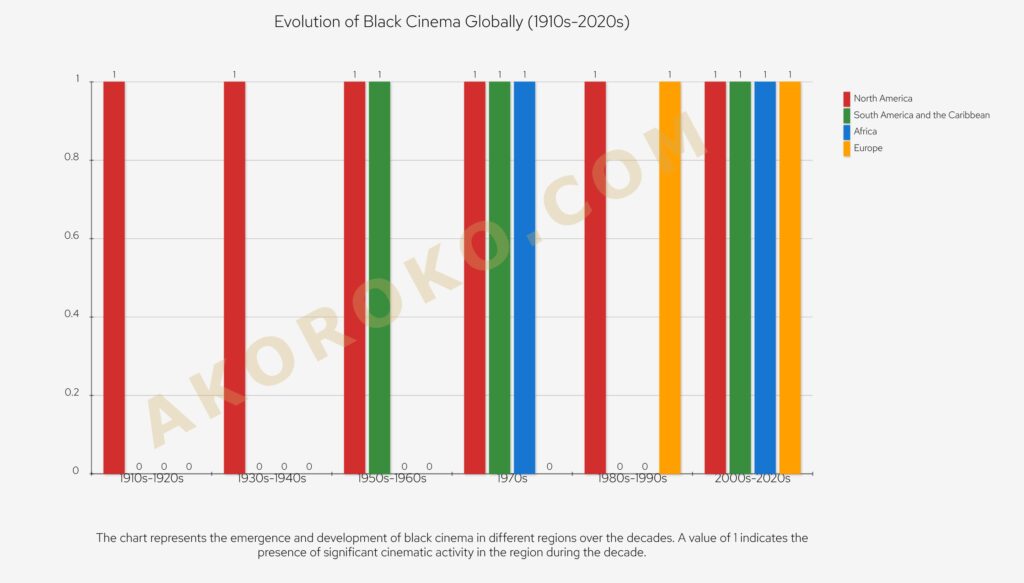

Context: Part of a larger project, here’s a rudimentary timeline providing a global overview of Black cinema activity (features primarily; not including Nollywood’s “video era”), highlighting key regions, from the 1910s to the 2020s.

The x-axis represents different decades; the y-axis represents different regions: North America, South America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Europe. Each bar corresponds to a decade and is divided into segments that represent the four regions.

If a region has a segment in a particular decade’s bar, it means there is noteworthy documented cinematic activity (again, primarily features) related to Black filmmaking in that region during that decade. For example, in the 1910s-1920s, the bar shows activity only in North America, indicating the birth of “Race Movies”. On the other end, by the 2000s-2020s, all four regions show activity, indicating the diversification and global evolution of Black Cinema.

The goal here is not only to illustrate the development of Black Cinema in different regions but also the interconnectedness of the timelines. To show how global events, movements, and trends have influenced Black Cinema, and how these regional cinemas have conversed with and influenced each other over time; a global conversation that has shaped the diversity and dynamism of “Black Cinema” we see today.

A quick spotlight on the Pan-Africanist cinematic efforts of Ossie Davis.

Note: This builds on existing data, including the shared knowledge of scholars on both sides of the Atlantic — a goal being to extrapolate and illustrate the development and interconnectedness of Black Cinema timelines worldwide, since the advent of cinema.

Davis was a pioneering figure in the development of Black Cinema, not just in the USA, but globally. His work, particularly in the films “Countdown at Kusini” and “Kongi’s Harvest,” sought to bridge the gap between African and African-American narratives.

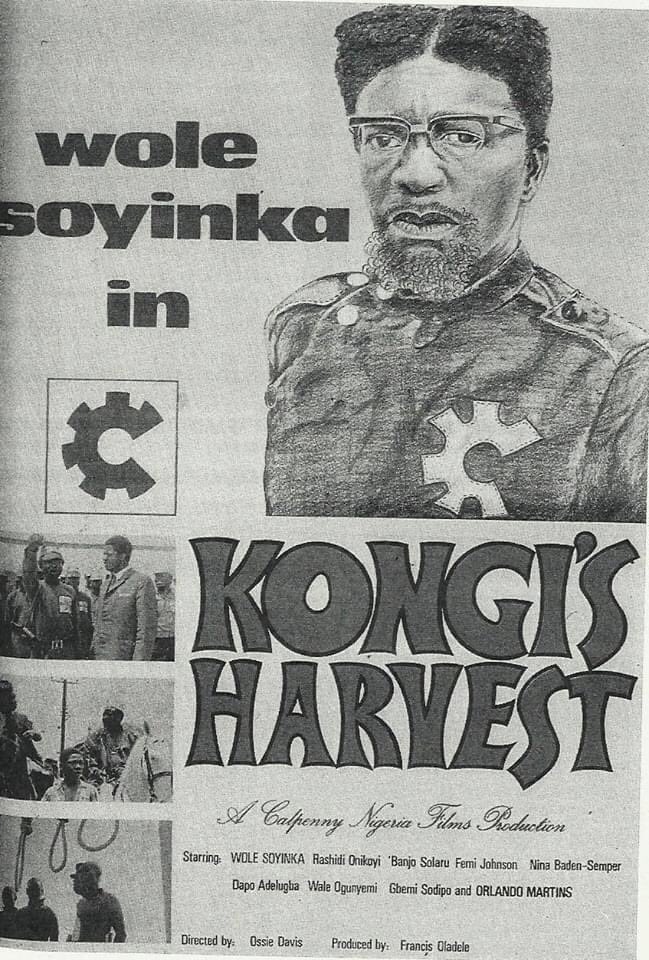

“Kongi’s Harvest” was an adaptation of a play by Nigerian Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka. The film, which Davis directed, marked one of the earliest documented collaborations between African and African-American artists in cinema.

Set in a fictional African country, the story revolves around the character of Kongi, a dictator who attempts to impose his will on a traditional African village. It delves into the power struggle between Kongi and the village chief, as well as the resistance of the villagers against Kongi’s oppressive rule.

Released in 1970, “Kongi’s Harvest” was produced by pioneering Nigerian filmmaker and producer Francis Oladele, who produced via his Calpenny-Nigeria Films Limited company, which is considered the first indigenous film production company launched in Nigeria, in 1965.

Despite facing numerous challenges, including logistical issues, cultural differences, and financial constraints, the team was committed to bringing Soyinka’s vision to the screen. The film was not well-received upon its initial release, but it has since been recognized for its historical and cultural significance.

Davis was a strong advocate for the development of a Pan-African film industry that would reflect the diversity and dignity of the continent and its diaspora; it was embodied in his direction of “Kongi’s Harvest”.

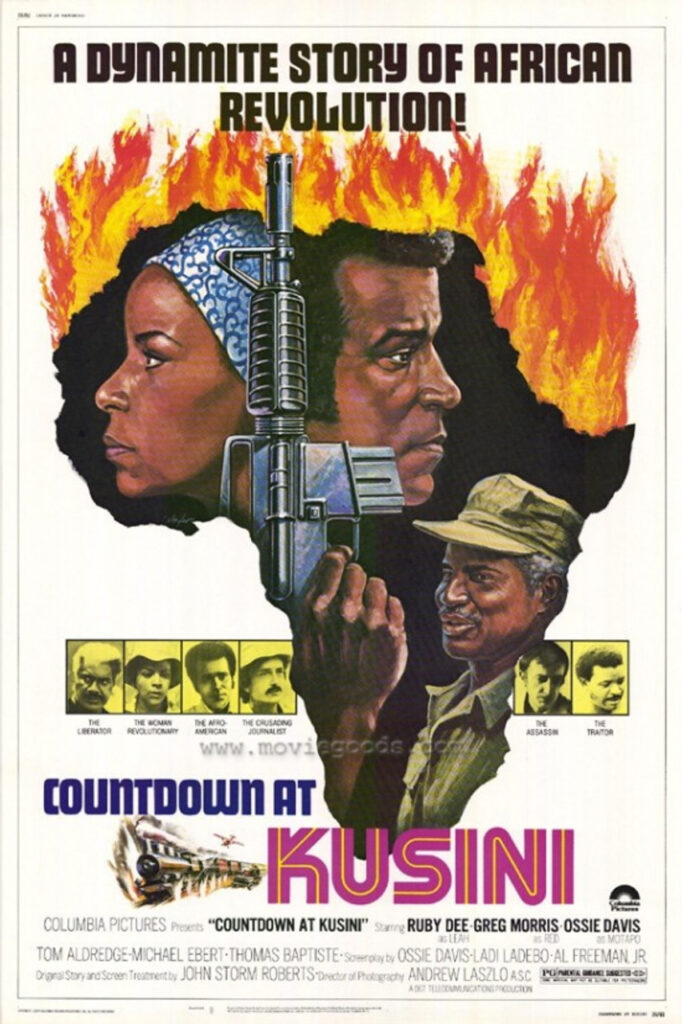

“Countdown at Kusini,” co-written by Davis, actor Al Freeman Jr., and Nigerian filmmaker Ladi Ladebo, was initiated by the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. Its story is the stuff of legend as the first major American film shot entirely in an African country, with a Black cast.

The Delta Sigma Theta Sorority made history by becoming the first Black women’s organization to produce a feature film with “Countdown at Kusini,” which Davis directed. It was developed as a counter-narrative to blaxploitation and negative representations of Blacks in media.

Shot entirely in Nigeria, “Kusini” centered on a rebellion against a corrupt colonialist government in a fictional African nation. To finance the film, all 85,000 members of the sorority contributed approximately $100 each to the endeavor, for a total contribution of $800,000!

The film received negative reviews from critics and it flopped at the US box office. Blame was spread around, including Columbia’s decision to release it against stiff competition, including “All The President’s Men,” “The Bad News Bears,” “Taxi Driver,” and “Sparkle.”

Among the Deltas who supported the film was Ruby Dee, and fellow heavies Leontyne Price, Lena Horne, Nikki Giovanni, and Roberta Flack to name a few. Prominent scholar Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman chronicled the project’s trials and triumphs in a 2007 paper you can read: [Link to the paper]

The two films share thematic and contextual connections that reflect Davis’s ambitions as a filmmaker and his engagement with African cultures and the Pan-African artistic movement. These themes align with Davis’s ambitions to use filmmaking as a medium to bring attention to the sociopolitical challenges faced by post-colonial African countries.

In the broader context of global Black Cinema, Davis’s films represent a crucial step toward a more inclusive representation of Black experiences. They were part of a larger movement in the ’70s/’80s that challenged the dominance of Western narratives and aesthetics in cinema.

This movement was influenced by various global events and trends, including the civil rights movement in the United States, the decolonization of Africa, and the rise of Pan-Africanism.

Here’s Davis discussing meeting with Francis Oladele, ambitions for Nigerian film, apprehension about taking on the project (he was still inexperienced as a director), directing a film in Nigeria, and more: “I wish I had a chance to make it now. I think I could do a much better job.”

If you appreciate our coverage here and on social media and would like to support us, please consider donating today. Your contribution will help us continue to do our work in coverage of African cinema and, more importantly, grow the platform so that it reaches its potential, and our comprehensive vision for it. Thank you for being so supportive: https://gofund.me/013bc9f2