Scattered across Twitter over the week or so, has been an ongoing debate about the origins of Nollywood and Nigerian cinema, with some conflating the two.

I’m not entirely privy to the roots of the discussion, or how widespread it is currently (it’s a recurring debate), but what ultimately drew my attention was a few mentions of the 1926 silent film PALAVER, which has been cited by some as an early example of Nollywood/Nigerian cinema.

However, others quickly corrected this, accurately pointing out that it’s actually a British colonial film shot in Nigeria, and not a Nigerian production, despite its potential status as the first feature-length narrative film made in the country (a detail that may require further historical research to verify, especially considering the complexities and gaps in early film archives).

The discussion has raised points about the origins and definitions of national cinemas, especially in the context of colonial histories — and PALAVER — that I will speak briefly to now.

Nollywood vs. Nigerian Cinema

Nollywood: The simplest definition of the term is that it specifically refers to the Nigerian film industry that emerged in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, characterized by *low-budget*, straight-to-video productions.

It is a significant cultural and economic phenomenon but, most importantly, is distinct from the broader history of films made in or about Nigeria, by Nigerians and non-Nigerians. Nollywood is a subset of Nigerian cinema; albeit a defining and dominant part of it.

Defining a national cinema is a complex issue that involves multiple factors, and it’s not as straightforward as simply considering the story, location, or nationality of the filmmakers, especially in our current globalized world.

By considering these various factors, one can arrive at a nuanced understanding of what constitutes “Nigerian Cinema.” It’s not a one-size-fits-all definition but rather a flexible framework that can adapt to the complexities of cinema cultures across Nigeria.

PALAVER in Context

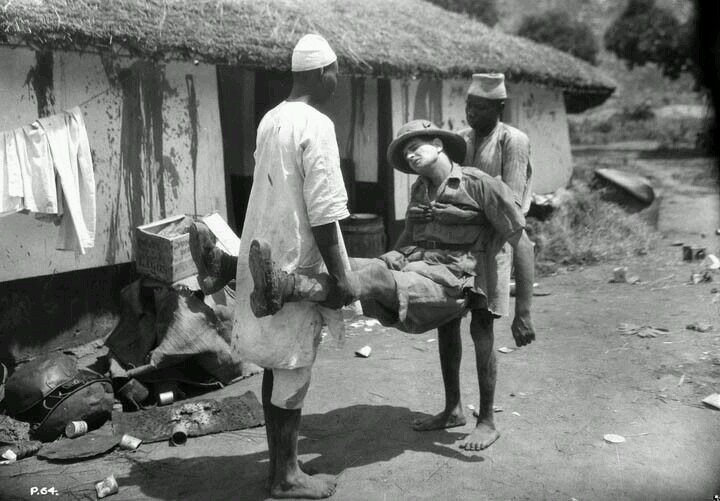

In the case of PALAVER (also known as PALAVER: A ROMANCE OF NORTHERN NIGERIA), while it was filmed in Nigeria and even featured Nigerian actors in speaking roles, it was a British production in terms of direction, production, and likely financing. One must also consider the context in which it was made. Therefore, it’s a British colonial film rather than a Nigerian film.

Directed by Geoffrey Barkas, and produced by British Instructional Films, PALAVER centers on the rivalry between British District Officer Peter Allison and tin miner Mark Fernandez, set in Northern Nigeria. Their conflict escalates into war after Fernandez bribes a local tribal king with alcohol to boost his failing mining operations. The film concludes with Allison successfully quelling the uprising and proposing to nursing sister Jean Stuart.

Films like PALAVER were often made with a colonial gaze, intended to serve the interests and perspectives of the colonial powers rather than the people being colonized.

Aligning with colonial narratives of the time, PALAVER is framed entirely from a British perspective, emphasizing the British role in “civilizing” Africa while portraying Africans as far removed from civilization and easily misled.

In the context of a struggling British film industry in 1926, PALAVER was presented as a beacon of British ideals and sentiments, aimed at rehabilitating the industry. Produced by Barkas and Stanley Rodwell, who had prior experience filming in the region, the film was lauded for its portrayal of British heroism in “civilizing” Nigeria.

Significance

However, its historical significance as perhaps the first feature-length narrative film shot in Nigeria can’t be ignored. It serves as a sort of precursor or footnote in the history of Nigerian cinema, even if it is not entirely a part of it.

It’s important to revisit films like this to understand the nuances of colonial narratives and their impact on modern cinema and culture.

Watch the entire 108-minute PALAVER below (it’s a silent film; i.e. no sound):

If you appreciate our coverage here and on social media and would like to support us, please consider donating today. Your contribution will help us continue to do our work in coverage of African cinema and, more importantly, grow the platform so that it reaches its potential, and our comprehensive vision for it. Thank you for being so supportive: https://gofund.me/013bc9f2