1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

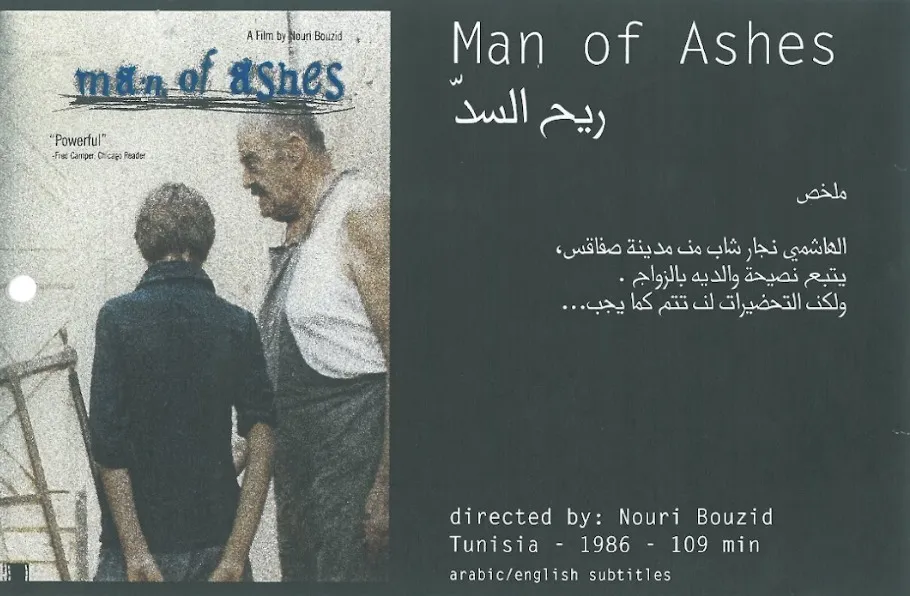

84 (TIE) – “Blue Velvet” (David Lynch, 1986) and “Man of Ashes” (Nouri Bouzid, 1986): It’s important to note that the neo-noir genre, characterized by dark themes, moral ambiguity, and stylistic elements, has been predominantly associated with Western cinema. African cinema, particularly before 1990 (a criteria of this series, but not a strict one), has been and continues to generally be more focused on social realism and sociopolitical themes.

Therefore, finding an African complement to a film like “Blue Velvet” poses quite a challenge.

That said, the Tunisian drama “Man of Ashes,” while not the best match for Lynch’s film, does delve into the hidden and often unsettling aspects of human nature, like “Velvet,” albeit through a different cultural lens and style.

In “Velvet,” Lynch’s signature surrealism and disturbing imagery create a nightmarish quality, exposing the sinister underbelly of American suburbia.

On the other hand, “Man of Ashes” explores the traumatic past of a young man, Hachemi, as he prepares for his wedding. The film uncovers hidden secrets and societal taboos, particularly around masculinity and sexuality.

Unlike “Blue Velvet,” “Man of Ashes” is more grounded in its approach, focusing on socio-cultural issues specific to Tunisia. Bouzid’s direction provides an intimate and realistic portrayal.

Despite their differences in genre and style, both films share a thematic focus. They challenge viewers to confront uncomfortable realities and question the veneer of their respective societies.

84 (TIE) – “Pierrot le fou” (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965) and “Pousse-Pousse” (Daniel Kamwa, 1975): Both use satire to critique societal norms and values. Kamwa’s “Pousse-Pousse” uses humor and irony to comment on urban life in Cameroon, particularly the challenges faced by a rickshaw driver in Douala, a major economic hub.

On the other hand, “Pierrot le fou” uses a similar approach to critique consumer culture and societal conventions in France.

While “Pousse-Pousse” may not be as avant-garde as Godard’s “Fou,” it also uses a non-linear narrative that adds complexity and depth, inviting viewers to engage more actively with the story.

Both films focus on individual characters who are navigating complex social landscapes. In “Pousse-Pousse,” the protagonist is a rickshaw driver dealing with the challenges of urban life in Douala. In “Pierrot le fou,” the main character is a disillusioned man who embarks on a chaotic journey with his ex-lover. Both are character-driven narratives that provide a window into the human condition, reflecting universal themes of struggle, identity, and self-discovery, although in very different cultural contexts.

84 (TIE) – Jean-Luc Godard’s “Histoire(s) du cinéma” (1988-1998) and Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s “Aristotle’s Plot” (1996): Both films are thematic explorations of cinema, with Cameroonian Bekolo’s “Aristotle’s Plot” specifically being a commentary on African cinema itself. It delves into the challenges that African filmmakers face, especially in the context of Western influence and expectations. This self-reflective approach resonates with Godard’s complex examination of the history of cinema and its relationship to the 20th century.

Furthermore, Bekolo’s film boasts an unconventional narrative structure and a critique of traditional storytelling methods, particularly Aristotle’s principles of drama. This aligns with Godard’s avant-garde approach to filmmaking and his willingness to challenge conventional cinematic techniques.

Stylistically, both filmmakers are known for their innovative and experimental styles. Godard’s work is often characterized by intellectual depth and complex montage, while Bekolo’s films often are a mix of genres and visual styles.

The contrast between the global perspective of Godard’s work makes the specific focus on African cinema in Bekolo’s film an intriguing complement.

88 (TIE) – “The Spirit of the Beehive” (Victor Erice, 1973) and “Po di Sangui” (“Tree of Blood,” Flora Gomes, 1996): Both are set in the aftermath of violent conflicts that affected their countries: the Spanish Civil War and the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence. Each film reflects on the trauma and silence of those periods, especially for children. They are both influenced by sources that explore creation, life, and death: Frankenstein and elements of Bissau-Guinean spirituality, folklore, and cosmology.

They use these sources to create original stories that explore identity, morality, and humanity via fragmented narratives that use flashbacks, ellipses, symbolism, and intertextuality to contrast reality and fiction.

For example, one film incorporates scenes from Frankenstein, while the other incorporates oral storytelling tradition, music, and dance.

They both have distinctive visual styles that create realistic, immersive, subjective, and emotional depictions of their settings and characters.

For example, “Spirit” emphasizes a girl’s imagination and curiosity, while “Sangui” emphasizes a man’s torment and despair.

88 (TIE) – “The Shining” (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) and “Aiye” (Ola Balogun, 1980): “Aiye,” co-produced by Hubert Ogunde and Ola Balogun, is a Nigerian film that delves into the life of a wealthy man tormented by his enemies who use supernatural powers to ruin his happiness. The film is rooted in Yoruba culture and explores themes of envy, power, and spiritual warfare.

Unlike “The Shining,” “Aiye” is more focused on cultural and moral lessons. The film’s narrative is complex and ambiguous, reflecting the intricate nature of Yoruba cosmology.

The complement between these two films lies in their exploration of supernatural elements and the darker aspects of human nature. Both films use surreal imagery to convey states of mind, although their approaches are quite different.

“The Shining” is a psychological thriller whose horror is more visceral and immediate, reflecting universal fears.

On the other hand, the horror in “Aiye” is more symbolic, reflecting societal values and conflicts, deeply rooted in supernatural elements that are tied to Yoruba spirituality. The film serves as both entertainment and a moral lesson.

88 (TIE) – “Chungking Express” (Wong Kar Wai, 1994) with “Adrift on the Nile” (Hussein Kamal, 1971): “Chungking Express” is known for its fragmented narrative that follows the lives of two Hong Kong policemen who are grappling with loneliness and heartbreak. The film’s storytelling, combined with its vibrant portrayal of urban life, creates a sense of disconnection and longing.

“Adrift on the Nile,” on the other hand, is set in Egypt and follows a group of friends who gather regularly on a houseboat to smoke hashish and escape the pressures of modern life. The film digs into themes of urban alienation, disillusionment, and the desire to connect with something meaningful.

Both films capture the essence of urban life in their respective cities, portraying characters who are adrift in a rapidly changing world.

The juxtaposition of these two films provides an opportunity to explore how different filmmakers approach similar themes, and how cultural context shapes the portrayal of universal emotions.

1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

If you appreciate our coverage here and on social media and would like to support us, please consider donating today. Your contribution will help us continue to do our work in coverage of African cinema and, more importantly, grow the platform so that it reaches its potential, and our comprehensive vision for it. Thank you for being so supportive: https://gofund.me/013bc9f2

Pingback: A Journey Through Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films and Their African Complements - Akoroko

Pingback: A Journey Through Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films and Their African Complements (90 to 100) — Akoroko - AKOROKO

Pingback: A Journey Through Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films and Their African Complements