1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

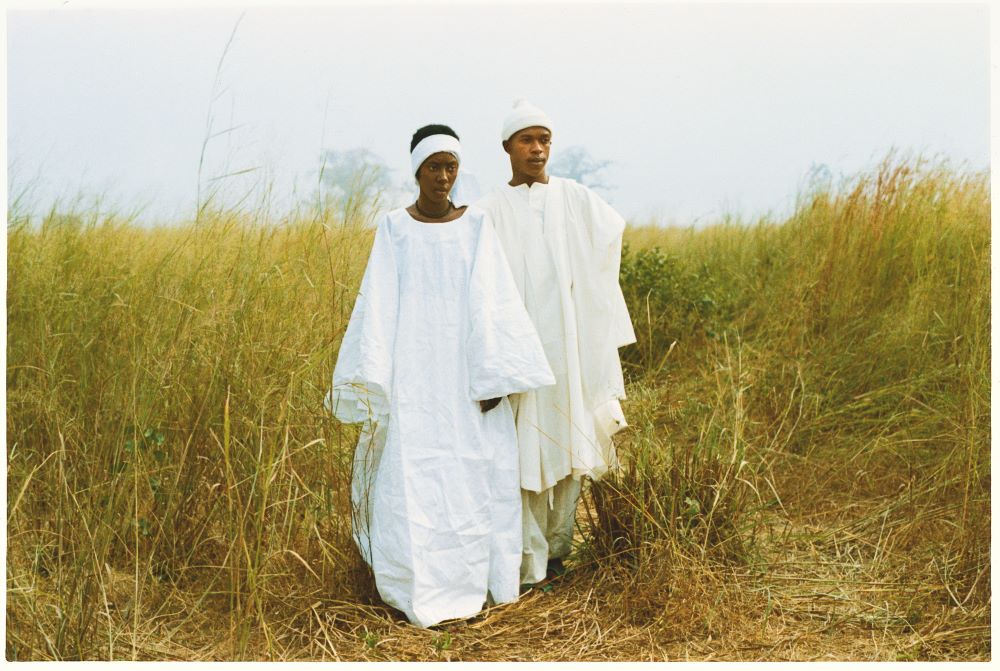

11. “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans” (F.W. Murnau, 1927) – “Atlantics” (Mati Diop, 2019): Both films are deeply rooted in their exploration of love and temptation. In “Sunrise,” a man contemplates murdering his wife after falling under another woman’s spell. Similarly, in “Atlantics,” a young woman named Ada is torn between her wealthy suitor and her true love, Souleiman, who has left Senegal for Spain by sea. Both films also incorporate elements of the supernatural, with “Atlantics” featuring spirits of the departed who return to settle scores. The boat journey in “Atlantics” can be seen as a metaphor for the emotional journey of the characters, much like in “Sunrise.”

“Atlantics” is available to stream on Netflix, Netflix Basic, and Mubi.

12. “The Godfather” (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) – “Tsotsi” (Gavin Hood, 2005): Both films delve into the world of crime and explore themes of morality, family, and redemption. In “The Godfather,” Michael Corleone is drawn into the family’s mafia business, leading him down a path of violence and power. In “Tsotsi,” the titular character, a young gang leader in Johannesburg, South Africa, experiences a moral awakening when he inadvertently kidnaps a baby during a carjacking. This forces him to confront his own violent past and offers him a chance at redemption.

You can stream “Tsotsi” on Tubi, Swank Motion Pictures, Amazon Prime Video, Plex, and other services.

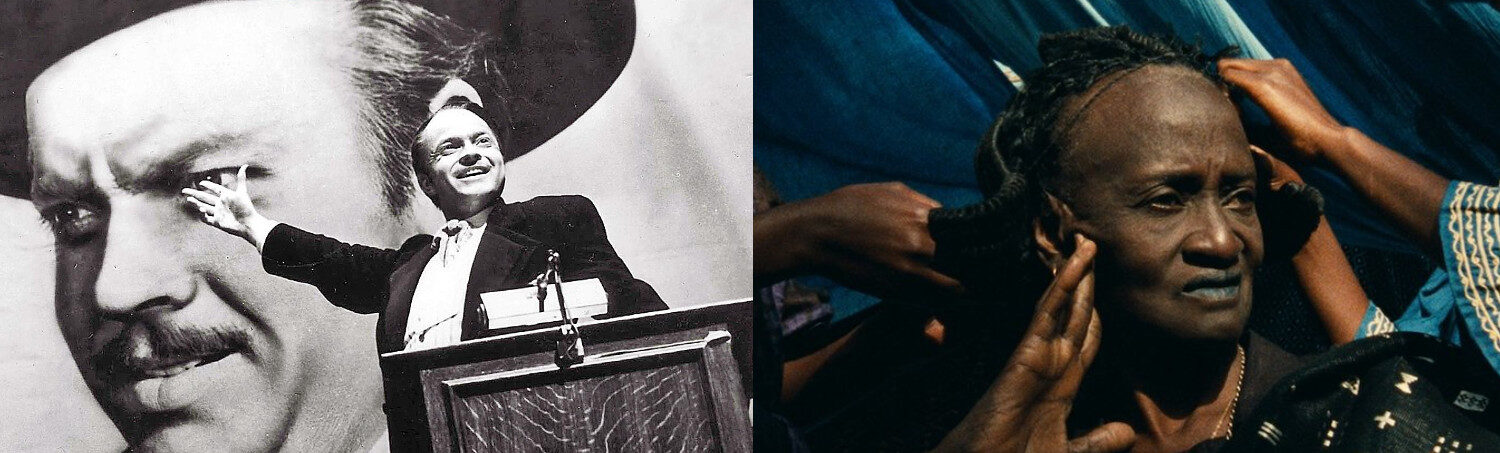

13. “La Règle du Jeu” (Jean Renoir, 1939) – “Xala” (Ousmane Sembène, 1975): Both films offer a critique of their respective societies and use humor and satire to expose the flaws and hypocrisies of their characters. “La Règle du Jeu” portrays the moral callousness of the French bourgeoisie on the eve of World War II. Similarly, “Xala” satirizes the corruption and ineptitude of the newly independent Senegal’s bourgeoisie, as represented by the protagonist El Hadji, who is struck with a case of impotence on his wedding night, a metaphor for his moral and political impotence.

You can watch it on Vimeo, YouTube, and the Internet Archive.

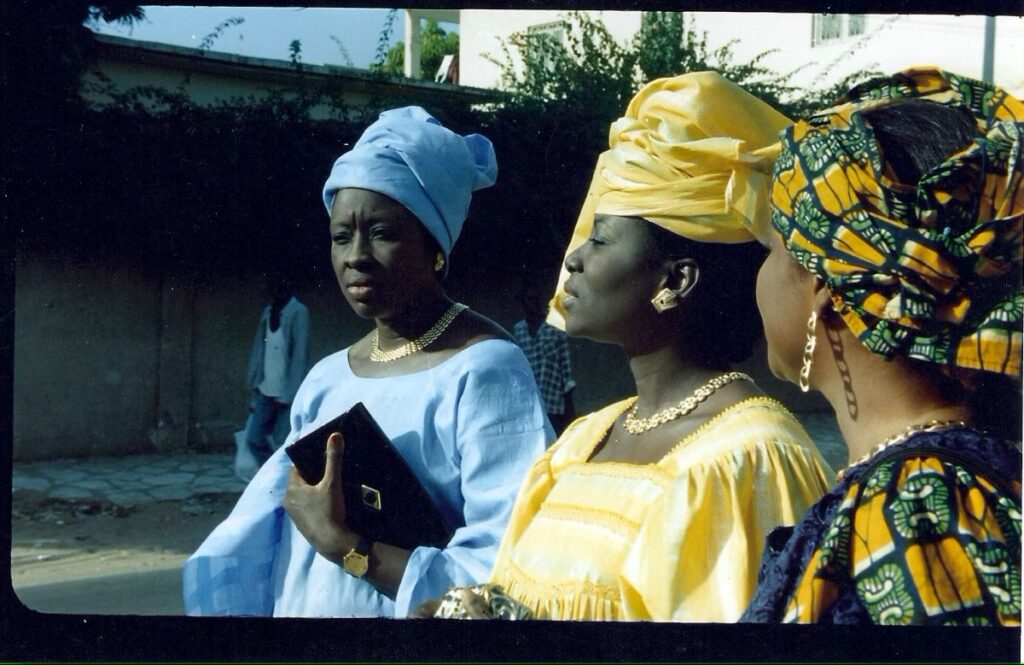

14. “Cléo from 5 to 7” (Agnès Varda, 1962) – “Faat Kiné” (Ousmane Sembène, 2000): Each film focuses on strong, independent women navigating societal expectations and constraints. “Cléo from 5 to 7” follows two hours in the life of Cléo, a pop singer in Paris, as she awaits the results of a medical test and grapples with her mortality. “Faat Kiné,” on the other hand, tells the story of a single mother in Dakar, Senegal, who, despite societal pressures, successfully raises her children and runs a gas station. Both films challenge traditional gender roles and highlight the resilience of their female protagonists.

“Faat Kiné” is not readily available to stream, but there’s likely a copy on YouTube.

15. “The Searchers” (John Ford, 1956) – “Finye” (“The Wind,” Souleymane Cissé, 1982): Each is a journey narrative set against dramatic landscapes. In “The Searchers,” a former Confederate soldier embarks on a quest to rescue his niece from the Comanche tribe, leading him across the vast landscapes of the American West. While, in “Finye” (“The Wind”), a young man from a rural village in Mali travels to the city to continue his studies, only to find himself torn between his village traditions and the allure of city life. The film explores Mali’s cultural and generational tensions, set against the backdrop of the nation’s stunning, open landscapes.

The film doesn’t appear to be streaming anywhere, but there’s likely a copy on YouTube.

16. “Meshes of the Afternoon” (Maya Deren, Alexander Hackenschmied, 1943): The body of work of Akosua Adoma Owusu, a Ghanaian-American filmmaker, who uses avant-garde, experimental, and documentary techniques to explore themes of identity, migration, Africa, and its diaspora. For example, her film “Me Broni Ba” (2009) is a lyrical exploration of hair salons in Kumasi, Ghana, using the practice of hair braiding on discarded white baby dolls from the West to evoke the “tangled” legacy of European colonialism.

Much like “Meshes of the Afternoon,” Owusu’s work is characterized by a surreal, dreamlike quality and an introspective exploration of identity. In each case, the filmmakers use experimental techniques to challenge traditional narrative forms.

Owusu’s films (primarily short films) have traveled on- and offline, drawing critical acclaim. It doesn’t appear any of them is currently streaming.

17. “Close-up” (Abbas Kiarostami, 1989): “Divine Carcass” (Benin, 1998) directed by Dominique Loreau, blends documentary and narrative storytelling, much like “Close-up” blurs the line between reality and fiction, creating a complex narrative that challenges the viewer’s perception of truth. “Divine Carcass” follows the fortunes of a 50-year-old Peugeot automobile offloaded in Cotonou, Benin. As it changes hands we get a glimpse into the lives of its successive owners. Its journey serves as a narrative device to explore various aspects of Beninese society, culture, and identity.

Its exploration of identity is particularly relevant when considering it as a complement to “Close-up” in which the protagonist impersonates a famous film director to gain the trust of a well-to-do family. It’s a deception and identity mirrored in “Divine Carcass” through the journey of the Peugeot. As it travels, it takes on different meanings and identities depending on the context, much like the protagonist in “Close-up”.

“Divine Carcass” is not available to stream. There’s likely a copy somewhere on YouTube.

18. “Persona” (Ingmar Bergman, 1966): Consider “Waiting for Happiness” (2002, Mauritania) directed by Abderrahmane Sissako, a contemplative portrait of life in a small town on the coast of Mauritania as it is caught between tradition and change. The film’s minimal dialogue and slow pace, create a sense of silence and introspection that might resonate with the themes and styles of “Persona.”

Additionally, in “Waiting for Happiness”, the characters are dealing with their own emotional struggles and are trying to find their place in a changing world, much like the characters in “Persona”. Both films encourage the viewer to engage actively with the film and to question the nature of identity and reality.

19. “Apocalypse Now” (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979): “Timbuktu” (2014), the second film on this list directed by Abderrahmane Sissako, tells the story of a cattle herder and his family whose peaceful lives are disrupted by Jihadists who impose their own harsh interpretation of Islamic law on the population. It’s a nuanced depiction of life under extremist rule, highlighting the absurdity and brutality of the situation.

“Apocalypse Now” is a war film set during the Vietnam War. It also explores the horrors of war and the descent into madness, albeit in a very different context and with a different narrative style. But both films explore the theme of war and its effects on individuals and communities, doing so in unique ways and within their specific cultural and historical contexts.

You can stream “Timbuktu” on MUBI, Fandor, Cohen Media, or for free with ads on Tubi TV.

20. “Seven Samurai” (Akira Kurosawa, 1954): “Five Fingers for Marseilles” (2017, South Africa) directed by Michael Matthews, could serve as an African cinema complement to Kurosawa’s classic — one of the most remade, reimagined, and referenced films in cinema history, starting with the Hollywood Old West-style remake “The Magnificent Seven” by John Sturges.

Coincidentally, “Five Fingers for Marseilles” is a Western-style film set in post-apartheid South Africa. The story revolves around a group of young friends who stand up to brutal authoritarian oppression in Marseilles, a remote South African township. As they grow older, their paths diverge, but when the now-estranged friends return to their hometown as adults, they find themselves in a battle to recapture its soul.

Similar to “Seven Samurai”, “Five Fingers for Marseilles” involves a group of individuals coming together to protect their community from oppressive people. The film also shares “Seven Samurai”‘s themes of loyalty, sacrifice, and the fight for justice.

Moreover, “Five Fingers” is a notable example of a film that blends the stylistic elements of a traditionally non-African genre (the Western) with a distinctly African setting and narrative, creating a unique contribution to world cinema.

You can stream “Five Fingers for Marseilles” on Philo, Tubi TV, iTunes, Plex, and Vudu.

1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

If you appreciate our coverage here and on social media and would like to support us, please consider donating today. Your contribution will help us continue to do our work in coverage of African cinema and, more importantly, grow the platform so that it reaches its potential, and our comprehensive vision for it. Thank you for being so supportive: https://gofund.me/013bc9f2

Pingback: A Journey Through Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films and Their African Complements