1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

I’ve had to be even more extensive in my research to find African films that could complement the next set of films in terms of narrative elements, style, structure, pacing, theme, and symbolism. However, finding strong matches has proven to be quite challenging due to the unique nature of several of them. But the beat goes on… I expect this to become increasingly challenging from here on.

Here are the next six titles on the list.

31 – “8½” (Federico Fellini, 1963) and “The Night of Counting the Years” (Shadi Abdel Salam, 1969): Fellini’s “8½” is a self-reflexive film that uses a non-linear narrative to explore the psyche of its protagonist, a film director suffering from creative block. It’s characterized by its dream sequences, flashbacks, and the blending of fantasy and reality, which mirror the protagonist’s internal turmoil.

“The Night of Counting the Years,” is an Egyptian film based on a true story about a tribe’s grave-robbing of the Pharaohs’ tombs in the 19th century. The plot revolves around a young man of the tribe who struggles with the morality of the tribe’s actions and ultimately decides to inform the authorities.

The film also uses a non-linear narrative and symbolism, set in a specific historical context, to explore universal themes of identity, heritage, and morality, as well as a focus on the individual’s struggle to reconcile personal desires with societal expectations.

The pacing in both visually arresting, awe-inspiring films is slow and contemplative, allowing the audience to fully absorb the symbolism and themes.

I only recently discovered “The Night of Counting the Years,” an African film that feels innovative and ahead of its time. But I still have much to explore in the realm of northern African cinema, which boasts richer cinematic traditions relative to its sub-Saharan siblings.

Watch “The Night of Counting the Years” below:

31 – “Psycho” (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and “The Sleepwalking Land” (Teresa Prata, 2007): Jahmil XT Qubeka’s “Of Good Report” would’ve been a strong choice that fits well as a complement to “Psycho.” The film’s narrative structure, with its twists and turns, mirrors the instability of Bates’ psyche.

But I already used it as a complement to another Hitchcock film on this list, “Vertigo” at number 2. And one objective here is to find suitable complements without duplicating titles, which is already proving to be challenging.

While it has been used as a complement for another film, Qubeka’s film stands out within the African cinema landscape, as a thriller with its own distinct genre and narrative elements. The film doesn’t have many direct equivalents or complements if any at all.

So, stripping “Psycho” down to its thematic essentials opens the door to a broader range of titles that align with those core themes in terms of capturing a lead character’s psychotic breakdown. And in the interest of time, I selected “The Sleepwalking Land” (Terra Sonâmbula, 2007), a film adaptation of Mia Couto’s novel of the same name, directed by Portuguese-Mozambican filmmaker Teresa Prata.

Set against the backdrop of the Mozambican Civil War, the film explores the psychological trauma faced by the main characters, haunted by their pasts, as they struggle to cope with the horrors of war. It’s a drama, and the atmosphere is not as unsettling as in Hitchcock’s classic. But it does blend reality with dreamlike sequences and visions, as the title suggests, to convey the characters’ psychological turmoil.

Additionally, symbolism plays a significant role in both films, that, along with surreal elements, serves as a visual language to convey the characters’ interiority.

While “The Sleepwalking Land” differs in genre and narrative style from “Psycho,” it offers complementary elements in terms of its exploration of the psychological trauma experienced by their main characters, offering insights into the fragility of the human psyche and the potential for darkness within us.

Watch the film below:

31 – “L’Atalante” (Jean Vigo, 1934) and “Zin’naariyâ!” (“The Wedding Ring,” Rahmatou Keïta, 2016): While both films differ in a cultural context and narrative approach, they both explore themes of love, desire, and the complexities of human relationships.

Vigo’s “L’Atalante” is a French romantic drama that follows the journey of a young couple aboard a barge, and their struggles to stay in love amidst the challenges of daily life and the longing for adventure. The film captures the tensions and conflicts within their relationship, highlighting the power of love to overcome any of life’s challenges.

On the other hand, “The Wedding Ring” takes us to Niger and presents a distinct perspective on love and relationships within the cultural context of a Tuareg community. The film centers around a young woman named Tiyaa, who returns to her hometown after completing her education abroad. Upon her return, she is confronted with the traditional practice of receiving a wedding ring, symbolizing her readiness for marriage. However, Tiyaa has other desires, specifically to pursue her own path and aspirations, which, as is typical in African cinema, leads to a clash with societal expectations and the struggle to reconcile personal desires with cultural traditions.

Additionally, “The Wedding Ring” explores the role of women in society, offering a unique perspective (the perspective of a Nigérien — different from Nigerian from Nigeria, a common mistake) on the themes of love and desire.

While “L’Atalante” and “The Wedding Ring” differ in cultural settings and narrative approaches, they share a common thematic thread of exploring the intricacies of human relationships and the complications of love and desire, in captivating ways.

“Zin’naariyâ!” (“The Wedding Ring”) is not available for streaming.

34 – “Pather Panchali” (Satyajit Ray, 1955) and “Lamb” (Yared Zeleke, 2015): Maybe the least challenging pairing of this set, “Lamb” is an Ethiopian drama that, like “Pather Panchali,” centers around a young male protagonist navigating the joys and hardships of an impoverished upbringing.

Zeleke’s “Lamb” tells the story of Ephraim, a young Ethiopian boy who is sent to live with his relatives in the rural countryside after the death of his mother. He forms a deep bond with his pet lamb, Chuni, as they navigate the challenges of their environment and the societal expectations placed upon them. The film explores themes of family and the preservation of cultural heritage in the face of adversity.

Similar to “Pather Panchali,” “Lamb” is a heartfelt portrayal of childhood experiences and the protagonist’s coming-of-age journey. Both films capture the innocence, curiosity, and resilience of children growing up in challenging circumstances while highlighting the profound impact of their environment on their lives.

Additionally, like “Pather Panchali,” “Lamb” authentically captures local landscapes while offering a unique glimpse into the struggles faced by people living in impoverished communities, while celebrating the strength and resilience of the human spirit, in the pursuit of a better life within an African context.

“Lamb” is available as a rental on Amazon Prime Video and Apple TV.

35 – “City Lights” (Charlie Chaplin, 1931) and “Sofia” (Meryem Benm’Barek, 2012): Once again, finding an equivalent or complement to “City Lights” from an African context, particularly as a silent film, is challenging. Silent films were not a prevalent form of cinema in Africa during the early 20th century. The development of African cinema was primarily influenced by the introduction of sound technology, and the majority of African films have been produced in the sound era.

However, while there may not be direct silent film counterparts from Africa, there are films from the African continent that explore themes of love, friendship, sacrifice, and the power of human connection in bustling city environments.

In this case, “Sofia” (2012), directed by Meryem Benm’Barek from Morocco, is a viable choice as a complement to “City Lights” due to its exploration of those themes.

“Sofia” tells the story of a young Moroccan woman who finds herself facing unexpected circumstances when she becomes pregnant out of wedlock. The film dives into the usual African storytelling complexities of societal norms and expectations, as well as the sacrifices and challenges that the protagonist and those around her must contend with in a bustling urban setting.

Similar to “City Lights,” Benm’Barek’s film offers a poignant portrayal of human relationships and the struggles faced by individuals in a bustling city. It sheds light on the dynamics of family, friendship, and societal pressures, exploring the sacrifices and choices made by the characters as they navigate their interconnected lives.

Directed with sensitivity and nuance, “Sofia” captures the essence of contemporary Moroccan society and offers a thought-provoking examination of the human condition.

“Sofia” is streaming on Tubi.

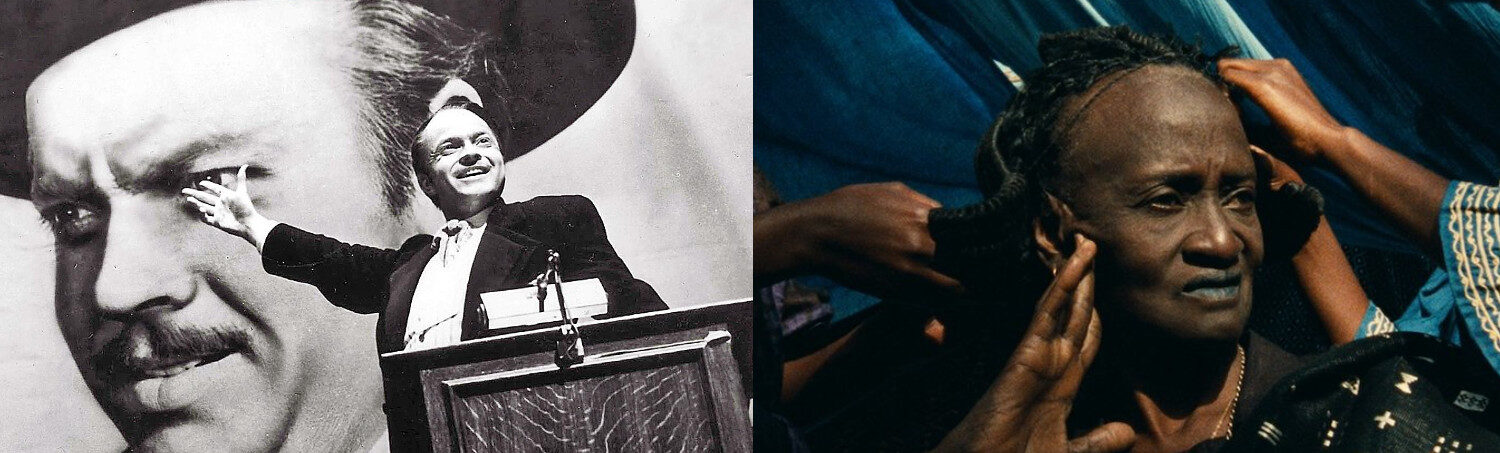

36 – “M” (Fritz Lang, 1931) and “L’oeil du cyclone” (“Eye of the Storm,” Sékou Traoré, 2015): Set in an unnamed African country/city ravaged by civil war, “Eye of the Storm” follows a young lawyer who is tasked with defending a former child soldier, now an older man, accused of war crimes. Lang’s “M” primarily focuses on the pursuit of a child murderer by both the police and the criminal underworld. There is no lawyer character in the traditional sense.

However, both deal with the topic of crime and justice, and how society responds to criminals who commit heinous acts.

There isn’t a direct contrast and conflict between law enforcement and vigilantes in “Eye of the Storm,” as there is in “M.” But there are elements of societal conflict and power dynamics within the film.

Additionally, both share a nuanced exploration of human nature and society, displaying both optimistic elements through the characters’ commitment to justice, and pessimistic elements through the portrayal of crime, corruption, and, in the case of “Eye of the Storm,” war, as well as the complexities of the pursuit of justice.

Both also show the futility and tragedy of the defendant’s fate, who are doomed by past actions and his present enemies.

Additionally, both films use sound and music as a way of creating tension and atmosphere.

“Eye of the Storm” is not available to stream.

1 to 10|11 to 20|21 to 31|31 to 36|38 to 45|48 to 54|54 to 60|63 to 67|67 to 75|78 to 83|84 to 90|90 to 100

If you appreciate our coverage here and on social media and would like to support us, please consider donating today. Your contribution will help us continue to do our work in coverage of African cinema and, more importantly, grow the platform so that it reaches its potential, and our comprehensive vision for it. Thank you for being so supportive: https://gofund.me/013bc9f2

Pingback: A Journey Through Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films and Their African Complements