The story of Nigerian cinema this century has largely been told through a handful of voices with international profiles – figures like Mo Abudu, Kunle Afolayan, and more recently, various individual deals with streamers like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, and other international studios. Their narratives, amplified by the mainstream media’s preference for simple success stories, have often obscured the intricate realities of making films in Nigeria.

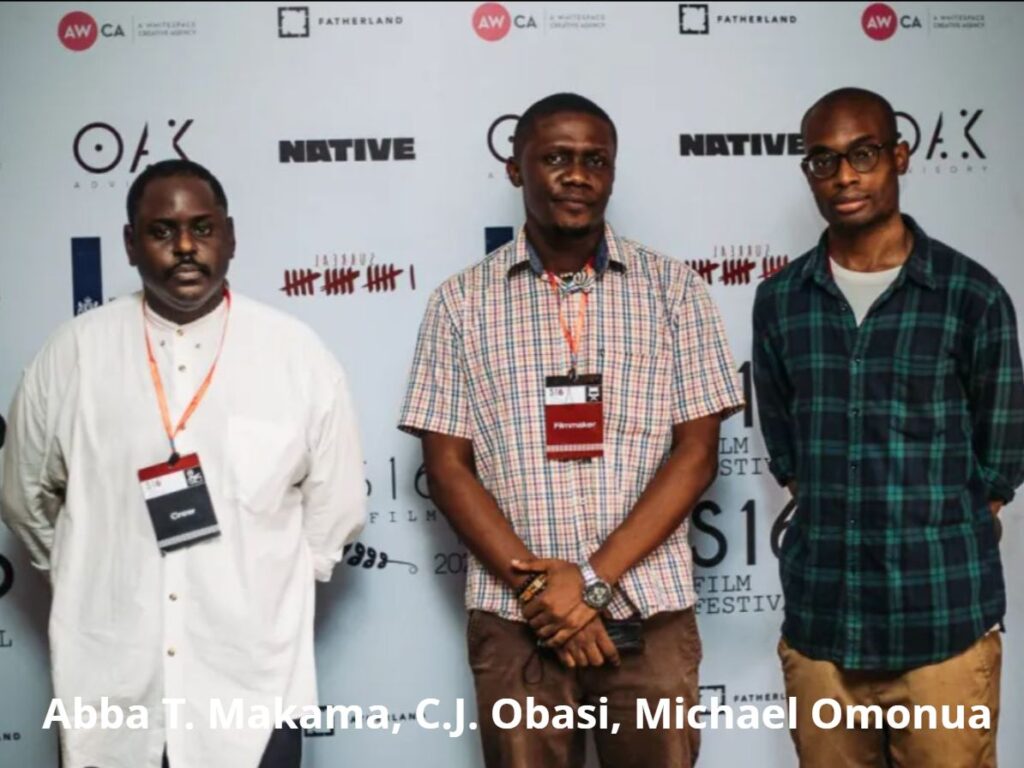

This makes the emergence of the Surreal16 (S16) Collective – founded by Abba T. Makama, C.J. Obasi, and Michael Omonua in 2016 – particularly significant. Their work, both as individual filmmakers and as a collective, offers insights into both the challenges and possibilities facing Nigerian cinema beyond the dominant “Nollywood” narratives.

The Reality on the Ground

“Filmmaking in Lagos is a nightmare,” states Makama plainly during a lengthy conversation I had with the trio in early November. “Corruption is normalized on every level.” The challenges begin with basic infrastructure.

Omonua, preparing for his upcoming feature “Galatians,” describes how even finding usable locations requires navigating a web of complications: “You’ve got to factor in sound because of generator noise… you may need to bring in your own generator, run a cable across the street, and that obviously adds a lot of costs.”

Then there’s the complex ecosystem of informal power structures. Every location requires negotiation with local “area boys” – though even this system is evolving. “They’ve gone corporate,” notes Obasi. “Instead of hostility, it’s like ‘How can we help? I have packages for you.'”

While there are signs of formalization – you can now get official film permits within 24 hours – the fundamental challenges remain. The lack of consistent institutional support means even successful initiatives often falter. Projects that start with promise frequently struggle to maintain momentum through political changes and shifting priorities.

The Streaming Mirage

The arrival of global streaming platforms in the late 2010s initially seemed to promise transformation. Obasi recalls being part of what was meant to be Netflix’s first Nigerian original series – a project that epitomized the platform’s ambitious early vision for Nigeria. “They flew into Lagos with their plane, Ted Sarandos [Netflix CEO] and others,” Obasi remembers. “There was this air of hope.”

The project itself was revolutionary in scope – a series about Orishas reincarnating as everyday people in a Lagos slum. The production team had resources unprecedented in Nigerian production. “This is how much money we had,” Obasi explains. “We were building our own Makoko. We got hectares of land and started building it, flooded it with water. We brought in a top production designer from South Africa who did the whole architecture.”

Makoko is a sprawling informal settlement with a mix of stilt houses over water and land-based structures.

Beyond the technical ambitions, the project represented something larger – the potential to set new standards for Nigerian production values and fair compensation. “I was looking at it beyond just making a great show,” says Obasi. “I was looking at the long-term effects it would have on the industry and the domino effect across the board as far as quality and people being paid well.”

Even the project’s announcement was choreographed for maximum impact. Sarandos revealed the series at a launch event attended by Nigeria’s entertainment elite. The reaction was telling – “You could hear a pin drop,” Obasi recalls, noting how the industry seemed stunned by Netflix’s choosing to work with alternative filmmakers rather than established names.

Then COVID-19 hit, and the project was suspended. Netflix’s subsequent strategy shifted toward commissioning multiple shows rather than focusing on fewer, more ambitious productions. This adjustment reflected broader changes in how streaming platforms approached content investment in Africa.

While they’ve seemingly scaled back any initial ambitious plans, Netflix remains active in Africa. Amazon Prime Video, by contrast, made a sudden complete exit within just two years of entering the market. The broader lesson may remain the same though – international platforms’ strategies ultimately prioritize economic efficiency over creative ambition.

“The only way they could have made a mark,” Obasi observes, “was to do quality shows that would pull subscribers in.”

The experience has been instructive for Nigerian filmmakers. Partly because Netflix has had a longer time to build its brand than its international competitors in Africa, it has become synonymous with streaming in many minds.

However, the realization that external platforms won’t provide the structural support Nigerian cinema needs is pushing filmmakers to seek more sustainable solutions. As Makama notes, “We’ve learned that everybody wants to come on board when things have picked up. To get things from the ground up… you need to get your money here in Africa and shoot your shit.”

Building Alternative Structures

Against this backdrop, Surreal16’s efforts to create sustainable alternative structures become particularly significant. In a Paris flat in 2021, still buzzing from winning the Boccalino d’Oro prize at Locarno for their first co-directed feature effort “Juju Stories,” the trio decided to address a crucial gap in Nigerian cinema.

Their manifesto’s 16 rules – including “No wedding films,” “No slapstick,” and “Genre films are encouraged” – read less like artistic restrictions and more like a practical framework for developing cinema beyond commercial formulas. However, it provided a creative foundation for a platform to actually showcase alternative cinema in Nigeria.

The S16 Film Festival emerged from this moment, though its path wasn’t obvious. “We just wanted to do something cool,” Makama recalls. “Even if it’s in a small room, people will come.” They had built a small but dedicated community around their work, and they believed in its potential to grow.

Their first venue was an old government printing press on Lagos Island – essentially an empty warehouse. They had to create everything from scratch: blacking out the space with cloth, installing lighting, bringing in chairs and mobile toilets. Their screen was a large advertising billboard. Despite these humble conditions, the festival drew between 200-300 people.

By their second edition, they had expanded to two locations, adding A Whitespace Creative Agency (AWCA) – a fixture in Lagos’ cultural scene for the past decade – for an exhibition honoring veteran Nigerian filmmaker Tunde Kelani.

The third edition was a major upgrade with their move to Alliance Française, finally providing proper cinema facilities and DCP capabilities. “We needed somewhere where people could come and watch, be relaxed,” says Omonua. “The image is maybe the most important thing.”

A key principle of S16 is paying screening fees to filmmakers – a practice uncommon in Nigerian festivals. “The moment we were able to get our venue paid for, it’s like okay so we freed up some cash – let’s give the money to filmmakers,” Omonua explains. “We wanted to make a festival that was filmmaker-first… that pushed the filmmaker to the front as much as possible.”

The festival has maintained consistent partnerships with the French and Dutch embassies while adding new supporters like the Goethe Institute. Rather than opening for submissions, they maintain an invite-only model to ensure programming aligns with their vision. “The programming could sort of narrow down tastes,” Omonua acknowledges, “but I don’t see the problem. There is Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, and the ACID parallel is also programmed by directors.”

Beyond screenings, the festival focuses on creating sustainable opportunities for filmmakers. Through new partnerships with Mostra de Cinemas Africanos (a Brazilian festival that foregrounds contemporary African films) and Open Doors (the Locarno Film Festival initiative), they offer workshops on festival strategy and industry networking. “We are trying to be a place where filmmakers can take themselves to the next level,” says Omonua.

This growth hasn’t come through external funding or institutional support, but through strategic partnerships and persistent effort. They’ve created a platform that serves both local filmmakers and connects to international cinema networks, becoming what Makama describes as “the number one spot that curates the best films coming out of the continent and internationally to Lagos.”

The Work Itself

The collective members’ films demonstrate the possibilities they’re fighting to create. Obasi’s “Mami Wata” (2023), his third solo feature, shot in lustrous black and white, became the first homegrown Nigerian film to compete in Sundance’s World Cinema Dramatic competition. Makama’s “The Lost Okoroshi” (2019), and Omonua’s “Rehearsal” (2021) similarly push creative boundaries while remaining grounded in Nigerian realities. “The Lost Okoroshi” premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in September 2019 and was later featured at the BFI London Film Festival the same year. Meanwhile, Omonua’s short film was in competition at Berlinale Shorts 2021.

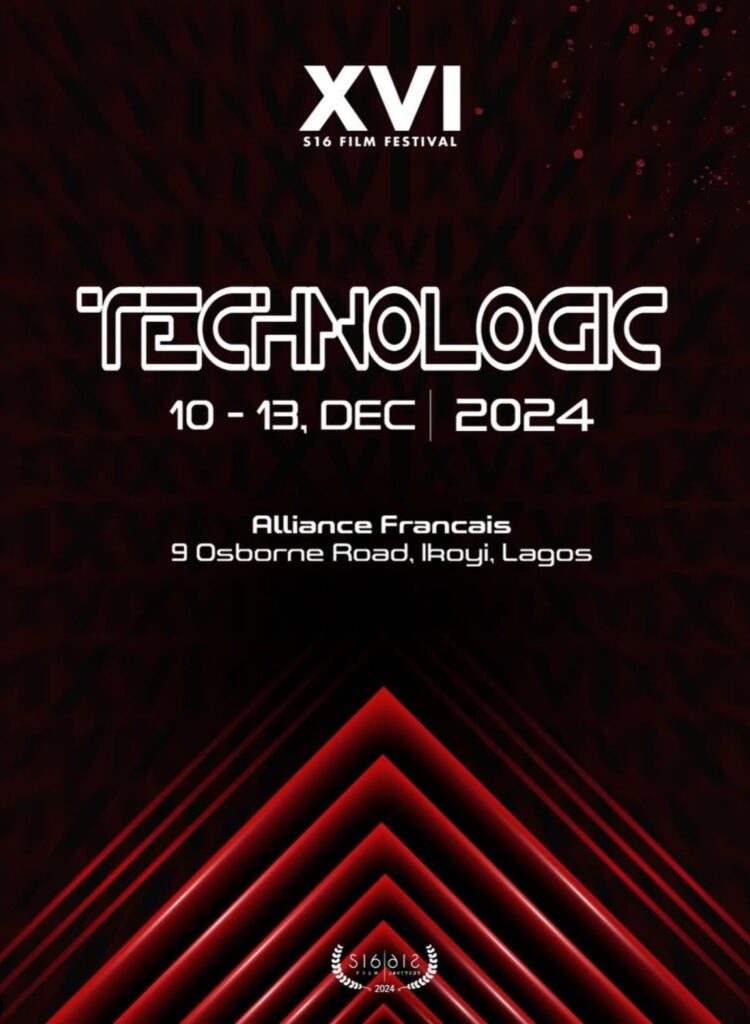

The 2024 edition of the S16 Film Festival, running December 10-13 at Alliance Française de Lagos, reflects their growing curatorial confidence. The program of sixteen films – their largest to date – opens with Zambian-Welsh filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl,” which premiered in the Un Certain Regard sidebar at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival before acclaimed screenings at Toronto and New York.

The festival closes with Cape Verdean Denise Fernandes’s “Hanami,” which launched in Locarno’s 2024 Concorso Cineasti del Presente competition before screening at the BFI London Film Festival.

These theatrical screenings in Nigeria – possibly the only ones both films will receive on the continent – underline S16’s role in bringing major contemporary African cinematic works to underserved African audiences.

Between these bookends, the program, themed “Technologic,” will showcase short films from emerging voices like Nigerians Tobi Onabolu’s “Danse Macabre,” which blends poetry, dance, and archival audio while drawing from Bergman and Abramovic, and Dika Ofoma’s anticipated “God’s Wife,” starring Onyinye Odokoro in an examination of misogyny in Catholic widowhood rituals.

The program also includes a retrospective screening of a remastering of Obasi’s 2015 film “O-Town.” Additionally, Makama’s “The Kids Are Okay,” shot two years ago, which explores the youth counterculture scene in Lagos, will also screen.

New partnerships with Mostra de Cinemas Africanos and Locarno’s Open Doors (recently announced a focus on 42 countries across the African continent from 2025-2028) have expanded S16 Film Festival’s international connections, manifesting in practical support like strategy workshops for emerging filmmakers.

It’s all a reflection of their commitment to promoting diverse African cinematic voices while building sustainable pathways between Nigerian filmmakers and the broader film world.

Looking Forward

The S16 crew maintains a clear-eyed view of the challenges ahead. They’ve learned not to wait for external solutions. “[South African producer] Steve Markovitz gave us the best advice,” notes Makama. “‘Don’t wait for Europe. Get your money here in Africa and make your films.'”

Yet, they also see signs of hope, particularly in emerging filmmakers. “I see the work, I’ve seen the short films,” says Omonua. “Even the ones who aren’t quite there, I can see what they’re attempting to do.”

Obasi is in the midst of developing his ambitious next project “La Pyramide: A Celebration of Dark Bodies.” He describes it as a “diaspora mystical voyage” that unfolds across three chapters. The filmmaker has already attached several notable actors to the film and is in the financing stage, working to secure the necessary budget to bring his vision to life.

Alongside this central project, Obasi revealed he has around 10 other film and TV projects in various stages of development, reflecting his strategy of maintaining multiple projects in the works to sustain himself as a filmmaker.

Meanwhile, Omonua is gearing up for his next feature film, tentatively titled “Galatians,” a satirical drama based on his award-winning short film “Rehearsal.”

With Makama producing, Omonua the duo is planning to begin principal photography in late 2025 or early 2026, as they continue to develop and prepare the project.

Meanwhile, Makama is currently focused on the business side of running the rapidly evolving S16 Film Festival, while shifting focus to documentary work. He says he’s taking a break from narrative fiction for the time being, with his latest effort “The Kids Are Okay” screening at the festival.

Their combination of pragmatism and possibility might be Surreal16’s most important contribution to contemporary Nigerian cinema’s evolution. They’re demonstrating that building new structures is possible, even without perfect conditions or local government or institutional support. It requires persistence, strategic thinking, and a willingness to start small and grow organically.

In doing so, they’re helping to write a new chapter in Nigerian filmmaking – one that exists beyond both the limitations of commercial formulas and the illusions of quick transformation through external intervention. The path they’re creating might be harder than the success stories usually told about “Nollywood,” but it might also be more sustainable.

“The game is the game, and we’ll continue to play it,” Obasi declares. Expressing hope for the future, he envisions a day when “one of us or someone within our circle becomes wealthy enough and with influence that can provide the means to do all this work that we and others want to do.”

Through it all, the Surreal16 Collective remains undeterred, poised to forge their own path. As Obasi asserts, “As we get older and more experienced, we can only bet on ourselves. The believers will come.”

If you enjoy deep dives into Africa’s diverse screen ecosystems, consider subscribing to Akoroko Premium for more insightful content like this: https://akoroko.com/subscribe/