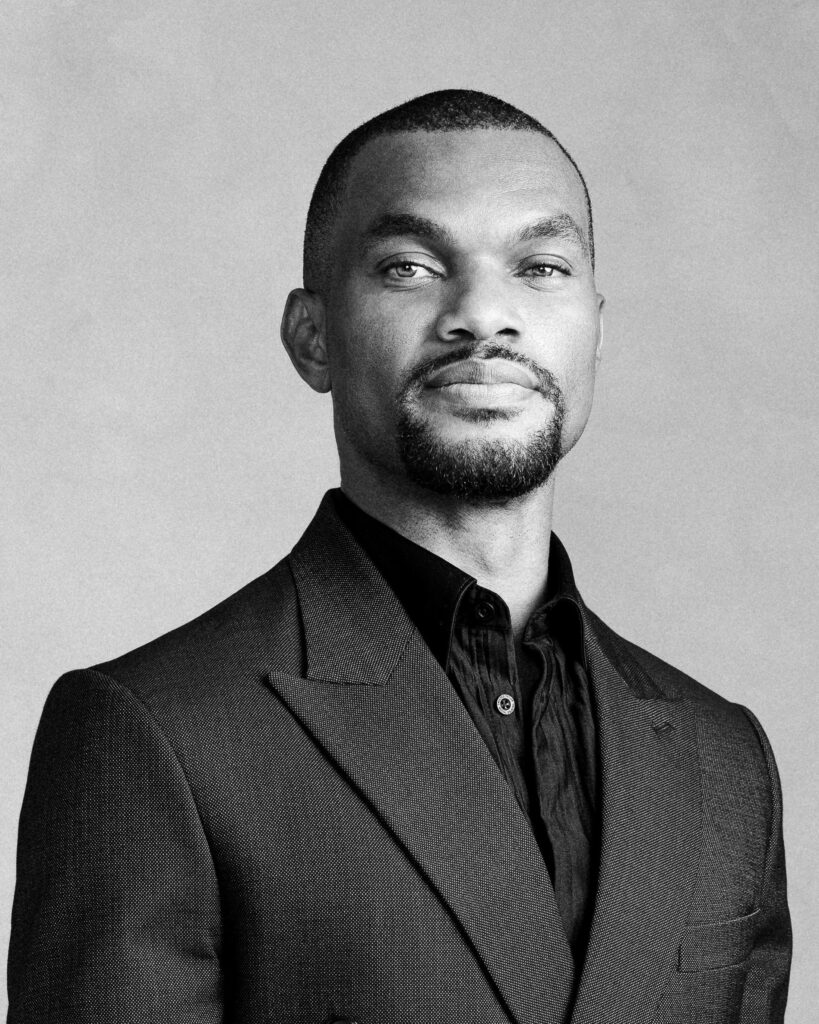

One week post the premiere of “The Black Book” on Netflix, its filmmaker Editi Effiong engaged in a long-distance conversation with Akoroko about the journey and impact of his debut feature. With a notable $1 million budget, partly footed by Nigerian tech investors, the film has become a talking point since its release on September 22, 2023.

In the conversation, Effiong shares “The Black Book’s” post-release ride, its global recognition, and his future plans amidst a busy schedule.

The dialogue touches on Editi’s cross-cultural experiences, the film’s financial journey, and its narrative that, per Netflix, has seemingly resonated on a global scale, shedding light on the evolving landscape of African cinema and promising horizon for Nigerian filmmakers.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Tambay Obenson: How are you feeling now that the film is out and generating headlines?

Editi Effiong: Today, tired. Yesterday, very tired. The day before, excited. And hopefully, we get back to a level where we can get back to work because this is taking a lot of time, but it’s the work that is required.

Tambay: What does that mean “get back to work”? What can you share on the record?

Editi: I mean that the reward for good work is more work. So the last couple of weeks, the world all of a sudden realized that an African title can actually scale globally. But I do absolutely love the fact that it opens very new opportunities for us as African filmmakers. I always thought we would do it, but maybe not on this scale. We do not need to have American faces. We do not need to attach Hollywood directors to African stories to make sure our stories travel. We have the capacity to do that here. And we have done it.

Tambay: Where are you based?

Editi: I’m a nomad at the moment. I’m in Lagos because I came here for the release of the film. Before then I was in London. And before then I was in Toronto. And when I go back I’m heading to Toronto and then to LA. I live in Toronto, but my experience as an immigrant is different from a person born in Canada. I spend a lot of time in the US and my experience there is different from anyone who was born there.

Tambay: How has that cross-cultural exposure influenced or had any effect on your career in terms of where you are right now in this moment, whether it’s international awareness, how you’re able to raise funding, whether it influenced how you told this particular story?

Editi: Actually it has had no impact. I lived in Nigeria for most of my life. I made this film in 2021, living full-time in Nigeria. I worked for 20 years in technology out of Nigeria. I own an advertising company. I own a tech company. And I built all of that in Nigeria. So, for example, with raising money, I put the most money into the film. Beyond that, we raised the million dollars in a family and friends round, mostly tech founders in private equity. And they came together to co-fund this. This is a Nollywood film. It sets a standard and marker for what a Nollywood film can be. But for all intents and purposes, it’s Nigerian money, it’s Nigerian storytelling, made in Nigeria by Nigerian actors and it’s gone around the world.

Tambay: Let me put it this way. I was born in Lagos and lived there for 15 years. My mother is Igbo and my father is Cameroonian. I’ve lived in the United States for 30 years. I still have extended family in both countries. But speaking as essentially an “outsider,” aware of the position I’m in, I would argue that the global exposure and experiences you gained from living in different places may have offered you different perspectives and potentially more opportunities.

Editi: I’ll say this. I’m represented by CAA.

Tambay: Was that before or after the film? Have you always been represented by them?

Editi: That was right after the film. “The Black Book” was a proof of concept for us. We do have a five-year plan and pictures in slate that we’re going to execute over the next five years. We’re doing this for the long term. I like to think that “The Black Book” would be the worst film I have ever made. And when I make the next thing, it will be the worst thing I’ve ever made. I think we are on a journey towards finding perfection.

Tambay: Of course, the expectation is that you’d be getting better as you go along.

Editi: Yes. But I’m very careful to highlight the fact that “The Black Book” was made in Nigeria, made of Nigeria. But the thinking for me is that if we tell stories that are universal, if we tell a Nigerian story well enough, the entire world will connect to it.

Tambay: Do you differentiate between Nollywood and Nigerian cinema? Do you call yourself a Nigerian filmmaker or a Nollywood filmmaker?

Editi: I have no problems being called a Nollywood filmmaker. I came out of Nollywood. When I made “Up North,” [Effiong executive produced the 2018 Tope Oshin film] it was called a Nollywood film. I didn’t argue with it. I’m not going to wake up one morning because I’ve made a film that’s received around the world and I’ll say, “I’m not Nollywood.”

Tambay: By the way, this is in the context of what seems like an ongoing debate around what is perceived to be an international stigma attached to the term “Nollywood.”

Editi: Now, I will make films internationally. We have plans to make films in the US market, for example. But I always want to tell a story with an African heart. Where I live in Toronto, Midtown, it’s largely white. There are no Nigerians. And so my friendships, the relationships I have to have are with people who have a completely different background. And so it affects how you move through the world.

Tambay: So then your international exposure has been of some influence, even if not financially.

Editi: Yes, I will make films around the world. But I was birthed by Nollywood. So I don’t have a problem being called an Nollywood filmmaker.

Tambay: When you were thinking of making “The Black Book,” were you thinking of it as a film for Nigerian audiences primarily? Or did you immediately mold it as a film that you wanted to see travel internationally?

Editi: I walked into the room the first day of the crew meeting and said, “Guys, I’m the least experienced person in this room. You all are pros.” I expected that if this was going to be my first time directing, and if I was going to do it well, I needed people who could challenge me, and help me do this properly. And I wanted them to know that there would be challenges, but, if we did it right, it was going to be the biggest film they’d ever made yet.

Tambay: The plan was always to sell it to a streamer. You were not even thinking theatrical first or a day-and-date release strategy?

Editi: Yes, it was always a streamer. I wasn’t going to cinemas.

Tambay: What prompted that decision?

Editi: Because there are only so many screens in Nigeria. It’s hard to recover a million-dollar investment in Nigerian cinemas. And it also reduces the value of the product, when you first go into cinemas.

Tambay: And you got back the million-dollar investment and, hopefully, a tidy profit when you sold it to Netflix?

Editi: I cannot speak about exactly how much I collected. But my investors are happy. I’m happy. That’s all I can say.

Tambay: How do you think the film compares to something like Jade Osiberu’s “Gangs of Lagos” in terms of scope and impact? Or, on the other side of the spectrum, you have C.J. Obasi’s “Mami Wata” which is enjoying a whole different kind of international success as more of an arthouse film.

Editi: In terms of scale, there’s nothing like “The Black Book.” I can say, commercially, Jadesola’s film was shot in Lagos in one contained location. The Black Book was shot in multiple locations across states. It’s not comparable. Jade was my script editor. We collaborate. So, I’m just saying simply there’s no comparison.

Tambay: Talk briefly about the scale; the locations, and logistics for context. An issue I continue to run into is a general lack of documentation, a lack of transparency broadly, across film industries on the continent. So it’s often a challenge to make substantive comparisons between one film and another.

Edit: Let me put it this way. A flight from Paris to Amsterdam, two major European cities in different countries, takes about an hour. To fly from Lagos to Kaduna is an hour and a half. It gives a sense of the size of Nigeria. Now, imagine having to coordinate a crew and their flight, but the next day, flight cancellations due to unforeseen weather conditions change your plans. So, the alternative is to fly the crew to Abuja, an hour and 10-minute flight, followed by a two-and-a-half-hour train journey to Kaduna. And then you consider road transport delays due to logistical issues and security challenges, especially armed robbery, making the coordination more challenging.

Tambay: Your take on the progression of streaming across the African continent. Speak to how you see this playing out, let’s say in the next five years.

Editi: What is very simple for me in my view, it’s that without Netflix and Amazon coming onto the continent, I would never have made “The Black Book. I’m a Nigerian filmmaker. I’m going to make films within the constraints of the industry. And five years ago I could only see a cinema exit when I made “Up North.” And then Netflix came and they provided a secondary window with the streaming service. And more people in the world have seen for the first time African stories on Netflix. And so that is the lens through which I view this.

Tambay: You’re platform agnostic?

Editi: I’m platform-agnostic, but I also have to admit that without this platform, we would not have had this many eyeballs see this breakthrough picture. And what seems to happen in terms of the audience is that if I have seen one Nigerian film and I feel really good about it, I might go look for other Nigerian films to watch. It also spurs the making of new pictures.

Tambay: When you were selling it to your investors, was that part of the pitch? That the film’s final destination was streaming?

Editi: Yes, it was. I had a plan A, and that was the plan. That we could make a film that was good enough to be sold to the streamers.

Tambay: I know you sold some Bitcoin to help finance this. How much?

Editi: It was around when Bitcoin went for about $54,000 each. We were already on set; we burned through a lot of the budget pretty fast because of COVID and other things. But I had to raise an additional $300K, so I put just about $100K of my money first and then raised the rest from my investors. But I’m the biggest investor at over 30% in total.

Tambay: How do you measure success beyond, let’s say, the Netflix numbers? Do you care about critical reception?

Editi: My fundamental belief is that films are made for audiences, and this is my measure of success. If I get my films seen by the most number of people, that is what I want. Some people will like the film. Some people will not like the film. It’s very subjective. I don’t belong to the arthouse group. I don’t belong to the big studio group either. And so it is important to me to only care about getting my film to audiences. I come from advertising and technology. It means that my eyes are on conversions.

Tambay: What are you working on? What can you share on the record?

Editi: I can say that the film is almost completely written in Hausa. I spent time traveling in the North, and really enjoy working in the North. That’s all I can tell you at this time.

“The Black Book” is now streaming on Netflix, featuring a cast including Richard Mofe-Damijo, Sam Dede, and Shaffy Bello among others. The story kicks off with a series of kidnappings and killings leading to a former gang member seeking vengeance.